Abenomics, the radical set of reflationary policies designed to (air)lift Japan out of its multi-decade slump, is approaching its first anniversary. Don't expect a joyful celebration.

On September 26, 2012, Shinzo Abe won the preliminary vote to run in the country’s national election, and three months later, on December 26, he became Prime Minister. Financial markets, doing their best to discount the rise of Abe and the promise of his aggressive reflationary policies, naturally began to move well in advance of his election. Japan’s currency was the first to respond and by October of last year had begun its astonishing journey downward. From above 126 USD/JPY, the Japanese yen fell (crashed, really) to 96 USD/JPY by May of 2013, and now rests at 99 USD/JPY. Nearly 30% of that decline had already taken place by the time Abe’s LDP Party secured a win in December’s national election.

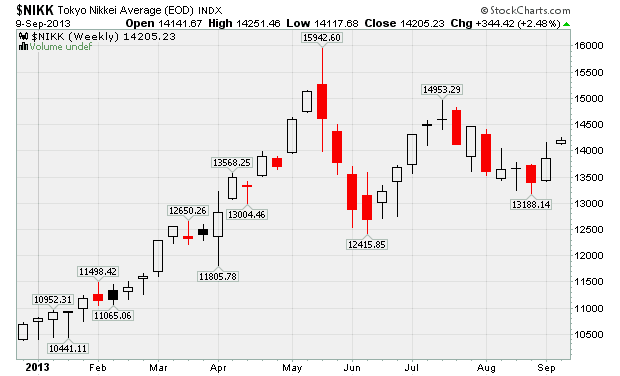

Meanwhile, the Nikkei was more hesitant to respond. However, almost immediately, the Nikkei, too, began its own astonishing move, breaking out of its trading range between 8400 and 9000 last Autumn and moving into a heroic frenzied top in May of this year, just shy of 16,000. It would be impossible to understate the sense of excitement from the financial press in New York and London at the prospect that Japan would finally, finally “do what it takes” to break the surly bonds of deflation. Keynesians, especially, spent much of the Winter and Spring in elation that, unlike the United States or Europe, at least one major actor in an otherwise stagnant OECD, would take the big risks necessary to confront the economic malaise that has more or less governed Western economies for a decade now.

However, as we approach the end of the first year of Abenomics, the cheerleaders and other hopefuls have fallen silent, as very little of note is happening in Japan’s economy.

The Guardian Economics Blog summed up the last year beautifully, in an even-handed but deservedly critical piece this August:

The honeymoon is over for Japan's prime minister, Shinzo Abe. The financial markets loved it when Abe announced a three-arrow strategy last year for ending his country's two decade struggle with deflation and sluggish growth. Share prices soared and the yen fell after the new government pledged large-scale quantitative easing, higher public spending and structural reform in a package dubbed Abenomics.

...But markets were left distinctly underwhelmed on Monday by Japan's latest GDP figures, which showed growth at 2.6% in the year to the second quarter of 2013, down from 3.8% in the 12 months ending in March. The rate of expansion was far weaker than expected and scotched the always rather fanciful hopes that Abe had found a magic bullet for Japan's woes. He hasn't.

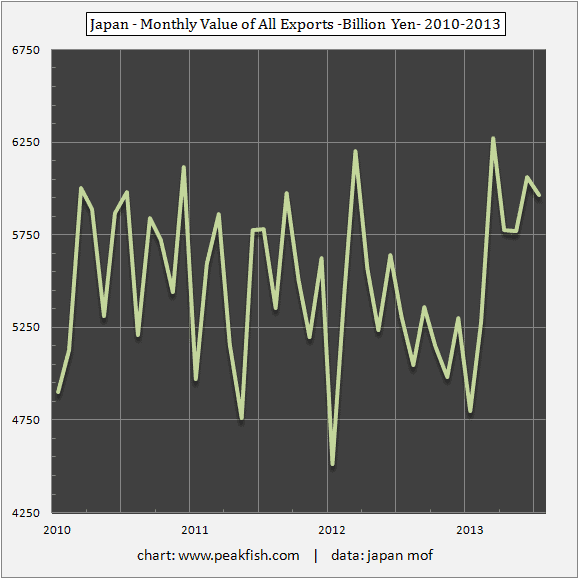

Probably no ongoing indicator better illustrates Japan’s, and Abenomics', failure to launch than the immoveable record of the country’s exports. Indeed, just about every policy initiative over the past few decades has had the increase in exports as its aim. Well, of course. Japan remains very anchored, industrially, economically, and culturally, towards its post-war experience as an exporter of manufactured goods. And every policy initiative has been met by the international trading and financial market community with a selling of JPY, in anticipation that all the stops would be pulled out by Tokyo to lift exports. Unfortunately, there has been very little movement in Japan’s exports over the past few years:

Upon closer inspection of the this chart, which tracks the value of monthly exports, Abenomics kicked off after Japan exports had started to decline more steadily in the early part of 2012. Having oscillated in range between 4750 and 6250 billion JPY per month, the early part of last year saw Japan exports threaten to fall out of range, below the 4750 billion level. Surely it’s not a coincidence that the Japanese electorate, then, would turn back towards a set of more aggressive policy measures. Especially policy measures designed to attack the currency.

The problem is that any highly discreet – and in this case, well advertised – move in financial markets generally overshoots, because what begins as a fundamental shift usually ends in purely speculative herding. (see George Soros on Reflexivity). Obviously, it made sense for the global leveraged speculating community to both front-run and also press the decline in the JPY, given the strongly declared intent of the incoming government. But the elevated level of excitement and anticipation can be sustained for only so long:

The Nikkei stock index seems to have discounted and then tracked two parts of Abe's Three Arrows Strategy by riding the massive monetary stimulus provided by a weakening JPY and anticipating yet (another) boost to public spending. The question is: Did the Nikkei discount the totality of Japan's big, new, strategy? In other words, by rising nearly 100% from the lows of 2012 near 8,000 to the high near 16,000 in May, did the Nikkei pretty much forecast the endpoint of Japan's latest economic experiment? If so, the Nikkei has probably seen its high for the year, and possibly even for this cycle.

If you disagree and believe that the Nikkei will exceed its May 2013 high, then you have to ask yourself: What set of additional policy measures would Japan need to announce in order to boost the Nikkei to new highs? Abe's Third Arrow, a set of structural reforms, is already greeted by markets just as you would expect: with a yawn. In this regard, Japan's relationship with international markets is pretty similar to any other country. Shock-and-awe fiscal and monetary policies are greeted immediately with a high degree of sensitivity in global forex, credit, and equity markets. Structural reforms? Not so much.

Japan and the Global Economy

Abenomics has run into several limits that no amount of huffing and puffing can overcome. Although it's true that Japan has been able to cobble together slightly better GDP growth this year (roughly in the range of 2.5%), the problem remains that Japan is part of a moribund OECD. Europe and the U.S. may have bottomed, but they're not exactly adding much to global growth, as recent macro data from the U.S. confirms. More difficult, especially as a manufacturer of finely engineered goods, cars, and other infrastructure equipment, is that Japan has also had to weather a slower rate of growth in the Non-OECD.

In truth, the totality of stimulus in Japan has essentially kept the economy out of recession, but not much more than that. In this way, Japan serves as a nice example of what faces the OECD – U.S., Europe, and Japan – as a whole.

Just this week, an advisor to Abe admitted that Abenomics has done very little. This assessment seems correct. While the waves of new policy measures have kicked up some dust and stirred up a lot of excitement – enough to allow cheerleaders to claim early victory – the data from Japan is very much like the rest of OECD: At best, we can expect sluggish, plodding growth at very low rates. From Bloomberg:

Koichi Hamada, an adviser to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, said it was too early to know whether Japan’s economy has turned the corner under the economic policies known as Abenomics. “Various economic indicators, including investment data, are picking up, but I’m not sure if they show a meaningful improvement,” Hamada said at an event today at Bloomberg’s Tokyo office. Hamada reiterated that a planned increase of the sales tax should be postponed or made in smaller steps, saying growth needs another year or so to reach its potential. Abe will decide whether to proceed with the move to rein in the world’s largest debt burden in early October after examining business confidence and revised growth data. The former Yale University professor said it’s questionable whether Japan needs to go ahead with raising the levy on consumers given the possibility that it could derail Abe’s economic agenda. Capital spending was unchanged from a year earlier in the second quarter after a 3.9 percent drop in the first three months of the year, a finance ministry report showed this week. Business investment by manufacturers fell 9.1 percent in the April-June period, a third quarter of decline. Gross domestic product preliminary data showed an annualized 2.6 percent expansion in the second quarter from the prior period, a third straight quarterly gain.

Although many observers continue to watch Europe and the U.S. for signs of a more sustainable recovery, it's actually Japan that is the pole star to the future of the OECD.

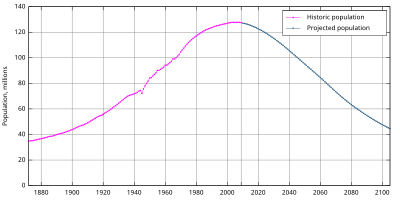

Why? Because Japan is where the most pure form of Keynesian stimulus has been tried for decades and where the heroic effort continues. Structurally speaking, Japan illustrates that once demographics, debt, and the loss of cheap energy and other resources come together, even the most historic set of reflationary policies can do little more than keep the system above the waterline.

Never Enough

It's poetic that Japan has once again embarked on such a journey just as the story of America's own post-crisis experience is being freshly updated. This Autumn marks the five-year anniversary of our financial crisis, a dramatic sequence in which several large financial institutions, starting with Lehman, failed. Echoing Japan, in each year since the 2008 crisis, it seemed that reflationary policy would be withdrawn only to be met by weakening or mixed economic data.

This September brings another staging of this tension as U.S. employment data has turned decidedly soft (or, if you prefer a different phrasing, U.S. employment growth has failed to get better). Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve has signaled its intent to pull back on its monthly purchases -- no, not a halt to monthly purchases -- which has caused tremors in global markets all summer, especially in emerging market currencies and in global interest rates. And especially in U.S. interest rates, which have seen the 10 Year Yield recently rise towards 3.00%.

The U.S. has its own domestic critics, and none more scathing than Paul Krugman, who is marking the five-year anniversary with a post explaining how a much stronger recovery in the U.S. could have been achieved. It ends with the resolute closing line, "by any objective standard, U.S. economic policy since Lehman has been an astonishing, horrifying failure." But there's more, in his September 5th column:

Set aside the politics for a moment, and ask what the past five years would have looked like if the U.S. government had actually been able and willing to do what textbook macroeconomics says it should have done — namely, make a big enough push for job creation to offset the effects of the financial crunch and the housing bust, postponing fiscal austerity and tax increases until the private sector was ready to take up the slack. I’ve done a back-of-the-envelope calculation of what such a program would have entailed: It would have been about three times as big as the stimulus we actually got, and would have been much more focused on spending rather than tax cuts.

And there you have it: The prescription for weak, post-crisis economies is simply more stimulus – multiples more. In Krugman's view, 3X more. In defense of Krugman, however, the central point is true: In capitalist systems with a reasonably functioning credit distribution mechanism, the provision of stimulus will indeed pull demand forward. This intertemporal demand shifting, which many critics assert accomplishes nothing, does in fact hoist large economies out of negative territory. That part of the argument is settled.

The more interesting question is: How productive and sustainable can these programs be, in a time of other limits – everything ranging from reduced world trade to higher resource costs?

Will the U.S. go the way of Japan? Not exactly.

In Part II: We're All Turning Japanese, we explore in more detail the various problems faced by the OECD, and in particular the hard limits which Japan is now running up against. Japan is unquestionably the leader in the long decline of the OECD, and while it may have some options, all choices which Japan could make seem to be increasingly radical.

But make no mistake; we need to watch Japan very closely. For as Japan goes, so will go the U.S. and E.U. economies.

Click here to access Part II of this report (free executive summary; enrollment required for full access).

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/abenomics-dismal-anniversary/