Students of Austrian business cycle theory are familiar with the term malinvestment. A malinvestment is any poor use of resources or capital, commonly made in response to bad policy (usually artificially low interest rates and/or unsustainable increases in the monetary supply). The dot-com bubble that popped in 2001? The housing bubble that similarly burst in 2008? Those were classic examples of malinvestment.

With this article, I'd like to introduce a related term: malincentive. While not part of the official economic lexicon, I consider 'malincentive' a useful word to describe any promise of short-term gain whose long-term costs outweigh any immediate benefits enjoyed. The temptation to urinate in one's pants on a cold winter day to get warm is a (perhaps unnecessarily) graphic example of a malincentive. Yes, a momentary relief from the cold can be achieved; but moments later, you'll have a much larger problem than you did at the outset.

Malincentives and malinvestment go hand-in-hand. In my opinion, the former causes the latter. As humans, we respond remarkably well to incentives. And dumb incentives encourage us to make dumb investments.

In this current era of central planning, malincentives abound. We raced to frack as fast as we could for the quick money, while leaving behind a wake of environmental destruction and creating a supply glut that has killed the economics of shale oil. Our stock exchanges sell unfairly-fast price feeds for great sums to elite Wall Street high-frequency-trading firms, and as a result have destroyed investor trust in our financial markets. The Federal Reserve keeps interest rates historically low to encourage banks to lend money out, yet instead the banks simply lever up to buy Treasurys thereby pocketing vast amounts of riskless free profit. The list goes on and on.

One particular malincentive has been catching my attention recently, one that feels especially pernicious because it does not seem easily reversible, if at all: For US employers both large and small, it's becoming increasingly less appealing to employ human labor.

The High Cost Of Labor

The cost of a human employee is much more than just the salary he or she receives. There's:

- base salary

- employment taxes

- Social Security/FICA (currently 6.2% on the first $90,000 of salary)

- Unemployment/FUTA (6.2% on $7,000 of salary)

- Medicare (1.45% with no salary cap)

- Workers Comp insurance (this can vary from 1% to 15%+ for every dollar of payroll, depending on the type of work the employee is engaged in)

- any benefits offered

- health insurance

- retirement plans (401k administration and/or matching)

- life insurance

- long-term disability

- vision/dental insurance

- dependent care assistance

- tuition reimbursement

The above combined typically result in a cost between 1.25-1.4x a worker's base salary. But this is not the 'all-in' cost.

There's also the cost of office space, equipment, management & supervision, training. Of HR services. Of paid time off. Of lost productivity if a worker turns out to be a bad hire. Simply put, people are expensive to employ.

But the situation is getting even worse. Employers of every size are experiencing a growing surge of additional costs in regards to their human workforce.

The recent push to dramatically increase the minimum wage over the next several years is currently being hotly debated. However, one thing that is not up for debate is that this rise will make the cost of labor substantially greater for businesses -- especially smaller businesses, as a greater percentage of their employees are at the minimum wage level. For instance, the hike to $15/hour now legislated for California and New York represents rises of 50% and 67% respectively from current levels. Businesses will not be able to absorb that labor cost increase without reducing headcount, raising prices and/or cheapening quality. Likely some combination of all three.

Similarly, the Affordable Healthcare Act requires businesses with 50 or more employees to offer health care coverage or face penalties:

Under the health care law, employers with 50 or more full time equivalents are considered "large businesses" and therefore required to offer employee health care coverage, or pay a penalty.

However, employers who are close to reaching 50 full time equivalents are encouraged to closely monitor their workforce, as reaching the threshold and not offering health care coverage can result in steep penalties.(Source)

What's the natural reaction to this if you're a small business owner? Do everything you can to keep headcount under 50 employees. Fire people if you must. Create part-time positions instead of full-time ones. Outsource. Automate.

The cost of complying with workplace safety regulations (estimated by some to cost US businesses over $65 billion per year) is jumping, too:

A 2016 “bombshell” is likely coming from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which is expected to increase fines more than 80%.

Thank Congress for the “catch-up” increase—OSHA’s first since 1990—that quietly got tucked into a bipartisan budget act in November. The law allows all federal agencies with civil penalties to update fines for inflation. OSHA can increase fines up to 82% and has until August 1 to do so, says Duane Musser, vice president of government relations for the National Roofing Contractors Association.

Musser considers the increase an almost a foregone conclusion. And based on testimony from OSHA assistant secretary David Michaels, that seems accurate.

(Source)

To these, add compliance costs for the Americans With Disabilities Act -- which do little to prevent predatory lawsuits designed to shakedown small businesses.

All in all, regulations have been calculated to place a burden in the $trillions per year on American individuals and businesses:

The Regulation Tax Keeps Growing

Blame Washington, not China, for the decline of American manufacturing

Updated Sept. 27, 2010 12:01 a.m. ET

This distribution of regulatory costs places small firms at a substantial competitive disadvantage. The cost disadvantage confronting small business is driven by environmental regulations, tax compliance, and occupational safety and homeland security rules.

In sum, individuals and businesses bear the burden of the $1.75 trillion cost of regulations, and small businesses bear a disproportionately large share of the compliance costs. Businesses must close, reallocate activity, absorb, or pass on the expense of complying with regulatory requirements.

Then, there's the hassle factor. Employees require oversight. Management. Development. They get sick. They take leave. They quit. Some do their jobs well; some don't. Things can get messy, and not infrequently, litigious.

The Drive To Automate

Given all the above, is it any wonder that businesses are desperately looking for ways to replace human labor with automation? Forget about profitability, it's becoming about survival.

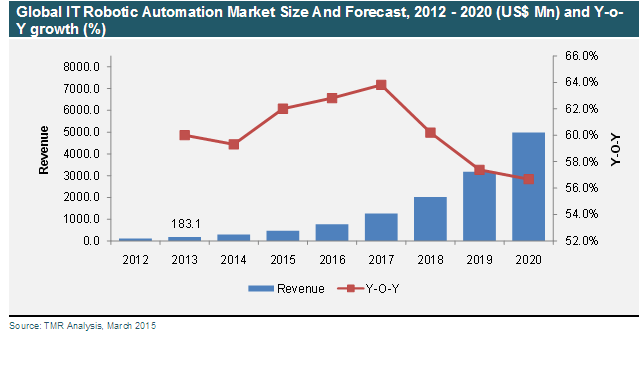

As a result, capital investment in automation (robotics, artificial intelligence, etc) is exploding:

Automation does come with higher upfront capital expenditures, but with the vast savings resulting from removing the fully-loaded costs of human employees, the profit incentive to swap bodies for bots is tremendous. And as robotic and AI technology quickly gets better and cheaper, the siren song only sounds sweeter over time.

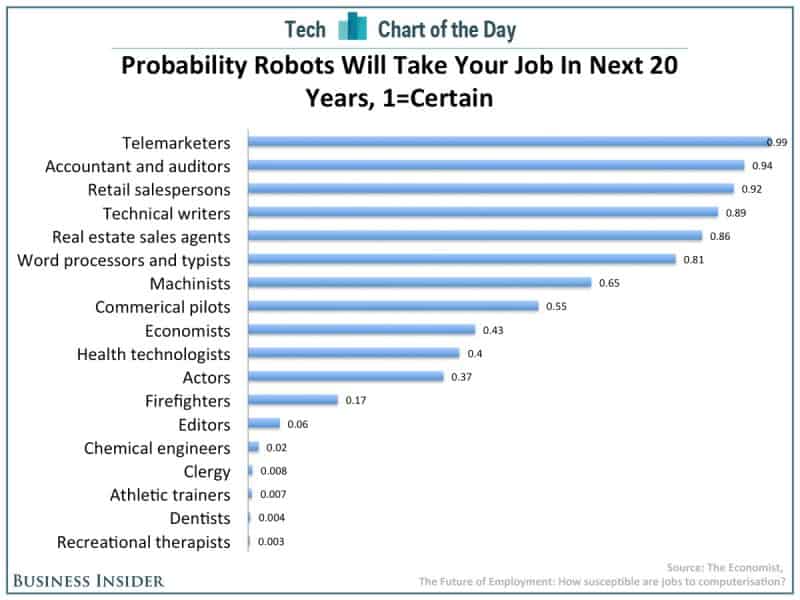

The categories of jobs that can be displaced by automation is impressive and expanding. Many industries once considered 'safe' now find themselves in the cross-hairs of progress. We have technology now capable of resolving real-world customer service calls, or landing rovers on Mars -- or a freaking comet, for that matter. The 2013 Oxford University study The Future Of Employment calculated that a full 47% of total US employment is at risk of being replaced by 'computerization'.

How safe is your job from being displaced by an automatic solution that performs it better, faster, cheaper -- without complaints, meals, vacations, sick days, bathroom breaks, benefits, regulatory obligations, and the rest?

Fuel On The Fire

Here at PeakProsperity.com, we write often about a coming 2008-style correction (or worse) as the multiple asset bubbles blown by the world's central planners go bust. Assuming for a moment that we're correct in that forecast, we'd see millions of jobs shed again as companies fight to stay above water.

What kind of investments will companies make in that kind of environment, when dollars are particularly dear? Answer: the kind that improve a business' cost structure -- that give it more runway, more time, to claw back to health. Automation will be at the top of this list. It's very easy to calculate the expected return of technical capex (i.e., making it easier for the C-suite to approve), benefits can usually be seen quite quickly, and the up-front investment cost can often be amortized on an accelerated basis (reducing the optical impact on the P&L).

As we've written, we think the worm has already turned, and that we are heading back into recession. There has been a stealth series of mass layoffs since the beginning of the year from major players in Tech, Energy and Finance - with Intel recently joining the list last week, announcing it's shedding 12,000 jobs.

The thing to realize -- in fact, the key point of this entire article -- is that jobs lost to automation don't come back. Human labor displacement is a one-way trip. Once an industry has invested in mechanical infrastructure and moved up the efficiency curve, it doesn't ever abandon that investment.

The High Cost Of Human Displacement

There is an intelligent debate to be had on the benefits of automation. Many have argued that the march of technology has always left future generations with more wealth and more meaningful work to do, as the laborious drudgery is increasingly mechanized.

Others warn that "technological unemployment" (a term coined by the economist Keynes) is not costless, and creates suffering among the lower-skilled workforce who lose their means of income. Keynes called technological unemployment a "disease" resulting from "our discovery of means of economising the use of labour outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labour.”

What is much less debatable is that displacing a large percentage of human labor without a plan in place to put that displaced labor to productive use is a sure-fire recipe for long-term crisis.

Our current trajectory has us hollowing out our workforce at an alarming rate. Unskilled labor needs a place of entry in order to build skills and work experience. Yet we are closing that door. Where are the young workers to get their start in a world where the largest employers simply don't need them?

We are already seeing signs that this hollowing out is well underway:

1 in 5 American households has NOBODY with a job living in it.

The labor force participation rate has been in steady decline since the Tech revolution started in the late 1990s:

The youngest workers, Millennials, are earning 20% less than the previous generation, and are drowning under $billions and $billions of education debt.

So many families are having difficulty getting by that nearly half of US households receive part or all of their income from the government:

The percentage of Americans now receiving a federally-funded “means-tested program” now stands at 35.4%. When you add pensions, unemployment, Social Security, and Medicare to the mix, the percentage of Americans relying on government for part or all of their subsistence is 49.5% of the American population.

(Source)

The statistics above show that we are badly failing at putting our current excess human capital to productive use. Even with today's 5% unemployment rate (yeah, right), we already have a national employment crisis.

What will things look like in 5 years, when millions of today's jobs have been vaporized by the automation wave?

Plan For The Inevitable

Automation is going to happen. And personally, given the extreme set of malincentives we currently subject businesses to, I expect the pace to only quicken from here.

So what to do?

From a societal standpoint, I think Nobel Economics Prize recipient Michael Spence has it right (full disclosure: Spence was the dean of my business school during my years there). He warns that the challenge of technological unemployment "will require shifts in mindsets, policies, investments (especially in human capital), and quite possibly models of employment and distribution."

It certainly will. The big question is: Will we, as a society, identify and adopt these mindsets/policies/investments/models in time? Sadly, my money is on that we won't. We haven't made much progress in doing so to-date, and the hour is getting quite late to act before crisis arrives.

Which is why, here at Peak Prosperity, we advise taking individual action to avoid being run over by the automation juggernaut:

- Skill up. Actively develop higher-order expertise, which will be the last frontier for AI to replace. Find a mentor to apprentice to, if you're able.

- Be entrepreneurial. The best way to avoid being let go by a company is to own it. Let the age of automation work for your benefit, not against it.

- Be a mentor. More than ever, the younger generation needs pathways to learn. Provide one.

- Find meaning in your work, as well as other areas of life. Automation may reduce your income, or eliminate it altogether. Don't let that crush your purpose in life. The Eight Forms of Capital framework we provide in our book Prosper! provides guidance on how to live richly even if your income becomes compromised.

- Support others. A lot of folks you know will likely be laid off as automation advances. Be there for them. Offer support. A lot of people are going to feel lost. Let them know the loss of a job does not equate to the loss of their worth as a person. They still have a valuable role to play -- it may just take a while to find it as we all figure out the new role for humans in this dawning Age of Machines.

~ Adam Taggart

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/automating-ourselves-to-unemployment/

One

One