The current Ebola outbreak, unlike others throughout history, is lasting a very long time; with cases now being reported on a variety of continents well outside of its equatorial African origin.

I’m not especially worried about Ebola striking me or my loved ones, for reasons I’ll explain in a moment. But I’m growing increasingly concerned about the government response to the outbreak.

So let’s spend some time understanding the nature of Ebola, specifically, and viral contagion, more generally. At the very least, Ebola can serve as an instructive reminder about how our society’s responses to a viral outbreak could prove to be at least as disruptive and damaging as the virus itself.

Ebola

While very often cited as being 90% fatal once contracted, Ebola is rarely that lethal. In fact, it was only that lethal in a single isolated outbreak. A 50% to 70% mortality rate is more common. As of Oct 10 2014, the latest outbreak had afflicted 8,376 and killed 4,024 -- a mortality rate of 48%.This places the Ebola strain responsible for the latest outbreak on the lower end of the Ebola lethality scale. Don’t misunderstand me: this is still a very deadly virus, to be sure. But it’s not a guaranteed death sentence, either.

Viruses come in a wide variety of types and shapes. But the general structure they all share is that they have some form of nuclear material, either DNA itself or RNA, housed inside of a protein capsule. Think of a peanut M&M, where the peanut is the genetic payload and the outer coatings serve both a protective purpose (while the virus is seeking a new host) and as the means of docking with a host’s cell.

That’s really all a virus is. A few proteins and some genetic material. No membranes, no sexual merging of genetic material, and no ability to replicate themselves all on their own. There are debates still ongoing today as to whether a virus should even be considered a living thing.

The life cycle of a virus is very simple. A virus particle will dock with a target host cell (most viruses are highly specific for the precise sorts of cells they will and won’t bind to), insert its genetic payload which hijacks the host’s replicative machinery, replicate the genetic payload wildly which codes for both new genetic material and protein capsule subunits, and then reassemble lots of intact virus particles which then escape the host cell to go and find other cells to infect.

Within a mammalian host, once a virus attack is recognized, an antibody response is mounted and the fight is on. As the virus particles escape the host cell (which is usually damaged or killed as a consequence of having been hijacked) it is vulnerable to being identified by a host antibody, itself a highly-specialized protein that will ‘dock’ with a virus particle more or less permanently (they bind together very tightly) and thereby incapacitate the virus’ ability to dock to a new host cell.

With lethal viruses, something goes wrong with this process. Either the virus replicates too quickly for the host to counter effectively, or the virus tricks the immune response into either too little or too much activity – both conditions which can end poorly for the host.

For example, the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918 preferentially killed those between the ages of 20 and 40. This was unusual because it’s exactly opposite the flu mortality patterns we normally expect, where the very young and the very old are the most susceptible.

The best prevailing explanation for this is that it was the very health and vigor of the patients that did them in. The Spanish flu (and other avian flu strains) cause the host body to unleash a ‘cytokine storm’ which is a very unhealthy, and sometimes lethal, positive feedback loop between immune cells and a class of attractor signaling molecules called cytokines. As more cytokines are released, say into the lung tissue, immune cells are attracted and can then release more cytokines, which attracts more immune cells, and so on. The place to which they are attracted becomes damaged by this overly-aggressive response of the immune cells and for the Spanish flu victims, this happened in the lungs, critically impairing respiration. Hence, the ‘healthier’ a host was, the more damage the Spanish flu virus caused.

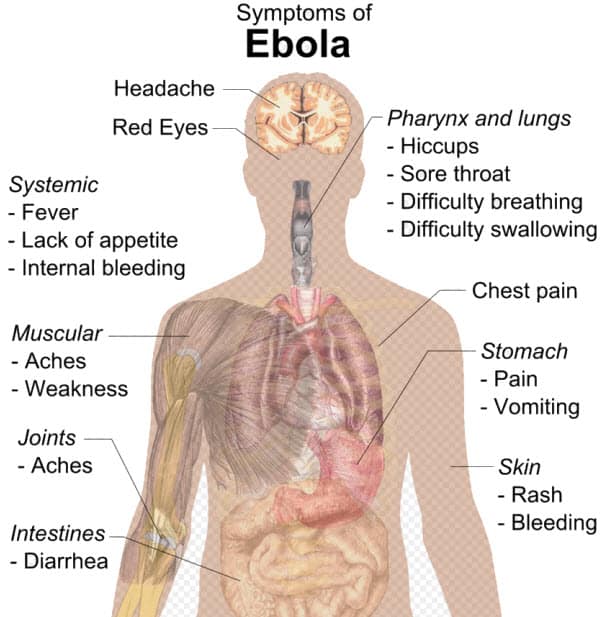

In the case of Ebola, the virus preferentially targets the cells that line the inner walls of blood vessels (a.k.a. endothelial cells) as well as white blood cells, a fact which helps to spread the virus throughout the body fairly rapidly, as white blood cells actively migrate system-wide.

Through a variety of mechanisms, the Ebola virus causes the endothelial cells to detach from the blood vessels and die, which compromises blood vessel integrity. This targeting of the blood vessels is why the Ebola virus is classified as a hemorrhagic fever. The patient’s blood vessels literally break down. That leads to the many visible symptoms of an Ebola victim, not the least of which is various burst blood vessels all throughout the body.

(Source)

Currently, it's thought that once exposed, an Ebola victim will incubate the virus for a period of up to 21 days before symptoms express. It's only once the victim is symptomatic that they themselves can transmit the virus and infect others.This characteristic of Ebola, more than any other, is why I don’t fear it overly much as a pandemic risk. A far more worrisome virus would be one that’s infective during asymptomatic stages of its host cycle, as is the case with HIV.

Early symptoms of Ebola include the sudden onset of fever, intense weakness, muscle pain, headache and sore throat. Unfortunately, that pretty much describes any reasonably intense flu, which complicates screening procedures and causes unnecessary worry among those who merely have the flu but worry about the possibility of Ebola.

Nonetheless, authorities have no choice but to take every traveling passenger with these very ordinary flu symptoms as a possible Ebola case. It’s a safe bet we’ll hear plenty in the coming days and weeks about Hazmat-suited response teams escorting sickly passengers off of planes.

A tip : if you have a fever, don’t travel. You’ll worry a lot of people unnecessarily. And you may end up in quarantine, really throwing your travel plans off the rails.

The Short-Term Risk

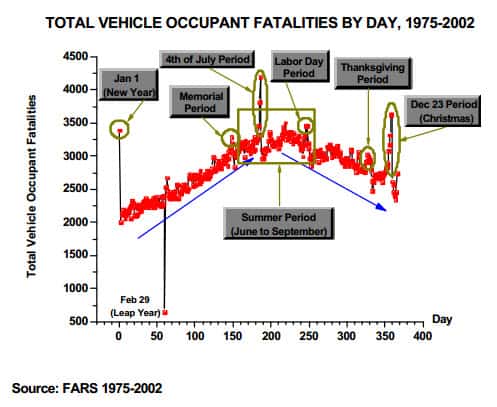

While gruesome and heartbreaking, the actual number of deaths by Ebola as well as the total number of people infected is very, very low compared to other hazards out there.Are you more worried about Ebola than driving to work? If so, you have those risks entirely inverted.

(Source)

In the above chart, there are 27 years worth of data contained in each data point. That means that if the chart reads 2,700 for a given day, then an average of 100 people died on US roads on that day each year out of 27.For the US, the above chart translates into ~33,000 vehicle deaths per year. Even in Africa where some 4,000 people have died from Ebola so far in 2014, America’s vehicle fatalities dwarf that current statistic.

Other communicable diseases such as HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, and diarrheal disease cause some 9 million deaths worldwide each year.

This is why I’m personally not that worried about Ebola striking me or my family here in the eastern US at this time. Nor would I be overly worried in Dallas, where the first two US-soil cases of Ebola command national attention. The odds of getting infected at this point are very low at the individual level.

The Longer-Term Risk

However, I do think that the reaction to Ebola, which could include ex- and inter-US travel bans and other economically and socially disruptive practices could be another matter altogether at this moment in time. While there is a small, but non-zero, chance that this Ebola strain could morph into something more virulent, there is a very good chance of a more Draconian government response developing.In Part 2: Prudent Precautions To Take Now, we dive into not only what damage to our civil liberties and livelihood these heavy-handed and poorly executed government responses are likely to be, but we also address the actions that individuals can take today on important questions like:

- Who is at risk of infection in the current ebola outbreak?

- What's the likelihood the current strain will morph into a more virulent form?

- What are the best steps to take today to reduce your vulnerability to a pandemic?

A small amount of preparing can make you much less vulnerable should (when?) that comes to pass.

Click here to access Part 2 of this report (free executive summary; enrollment required for full access)

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/ebola/