Most of us dress ourselves each morning with garments that were grown, processed, designed and sewn by an anonymous supply chain. A combination of animal, plant, machinery, imagination, and technical skill came together to clothe you, but it is rare to have connection to any of these real life elements.

It is the goal of one central Californian community's members to put a face on their wardrobes, and to uncover, develop, and build a new way of engaging with the textiles of their lives. A bioregional supply chain known as a Fibershed is being grown out of a region with a 150 mile diameter — the epicenter just north of San Francisco.

The project aims to bring a thriving local alternative to conventional textile manufacturing systems and to support communities in reviving, sustaining, and networking their raw material base with skilled design and artisanal textile talent.

The Rationale for Domestic, Sustainably-Made Textiles

This DIY revival is steeped in an awareness of the global economic, social, and environmental realities brought forth by conventional textile supply chains and is a response to the following situation:

- After agriculture, the textile industry is the #1 polluter of fresh water resources on the planet.

- The industry's carbon footprint has been deemed the ‘elephant in the room’ by many in the trade –- ranking as the 5th largest polluter in the United States, where only a fraction of the industry even remains.

- The chemical cocktail used to soften, process, and dye our clothing is attributed to a range of human diseases – including chronic illness and cancer.

- Even the most ‘eco-friendly’ synthetic dyes contain endocrine disrupters, and the most commonly used dyes still contain heavy metals such as cobalt, chrome, copper, and nickel.

- Labor is sought for cost, first and foremost – not quality -- leading to massive exploitation and many unstable jobs.

In 1965, 95% of the clothing in a typical American’s closet was made in America. Today less than 5% of our clothes are made here. Unfortunately, this huge movement of the industry was not prompted by a desire for higher standards of production, economic equity for laborers, or tight environmental regulation. It was done to circumvent the policies, unions, and costs associated with doing business on shore.

We have off-shored the effects of our consumption, which has led to a great disconnect of the actual environmental and social costs of our clothing.

The Fibershed Experiment

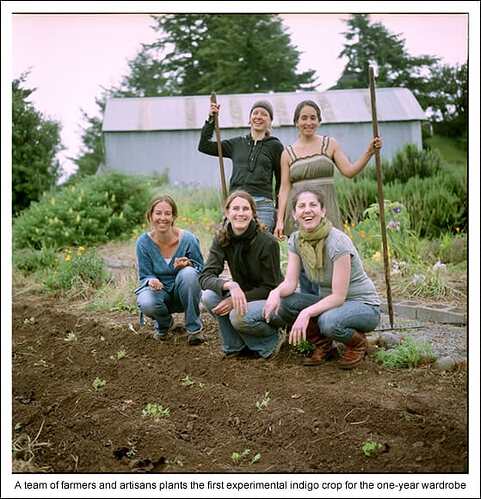

The Fibershed project began in 2010 with a one-year challenge to create an experimental wardrobe from fibers, dye plants, and local labor all sourced from within 150 miles of the project headquarters. As the wardrobe was constructed over the one-year period, so,too, was the network of artisans and farmers responsible for its creation.

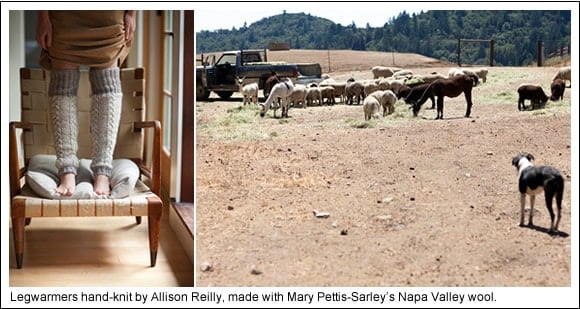

The garments were primarily hand-constructed. The rural region proved to be rich in raw materials: word-class alpaca, the finest merino wools, color-grown cottons, and the softest angora. The design talent from the urban sector was abundant in skills, experience, and passion. Many of the essential elements necessary to engage a bioregional supply were in place: the animals, plants and people.

However, the necessary machinery to produce conventional clothing was nowhere to be found. Most manufacturing had disappeared in the wake of NAFTA and the FTAA free trade agreements. Without the necessary equipment, the group relied on time-honored skills that artisans throughout time have relied upon to make cloth: spinning wheels, knitting needles, and floor looms.

The quality of the craftsmanship that emerged from the designers and makers proved to be an unending wellspring to which we have yet to find a limit. Textiles continue to emerge from the local fibers (even beyond the experimental wardrobe), and the process of seed-to-skin creation continually affirms the incredible beauty and depth of locally farmed clothing.

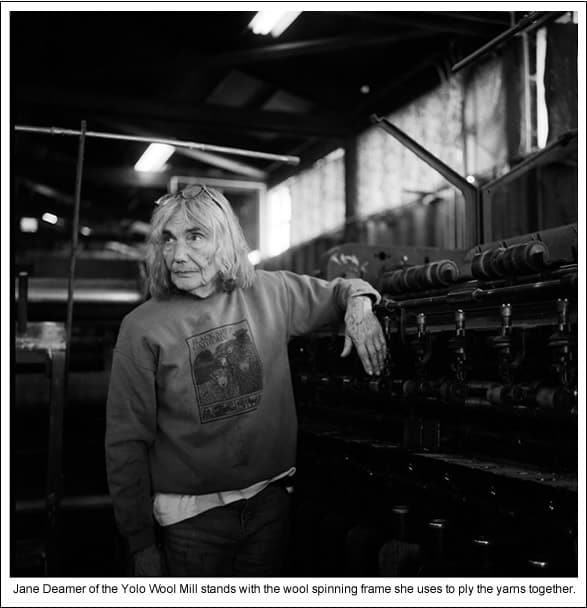

The project specifically matched a local artisan with a local farmer to collaborate to make a garment. During this process, we identified our skill base and mapped many of the farms in the region. As we documented ourselves, we identified our collective reliance upon one important nexus within the community: the last remaining wool mill, the place where fiber becomes yarn.

The machinery had survived the great offshoring of jobs and equipment during the emerging global economy of the 1980’s and 1990’s due to the tenacity and heart of its owner, Jane Deamer. She had managed to remain in business with the support of small fiber producers, making yarns for the hand-knit and hand-woven community. It was Jane’s processing equipment that provided the bulk of the yarns that were utilized for the one-year wardrobe and continues to supply our region with homegrown raw materials.

The one-year wardrobe gave us the opportunity to test the wearability of the wool yarns and explore which flocks of sheep were best suited for specific garments.

We discovered uses for raw materials that initially we had no understanding of. For instance, we solved all-weather wearability problems with renewable natural fibers -- in instances where most modern Americans would pull the polypropylene raincoat from the closet, we were able to create an all-weather wardrobe without the use of any petroleum-based fibers, and forewent the use of any synthetic, coal-tar-based dyes.

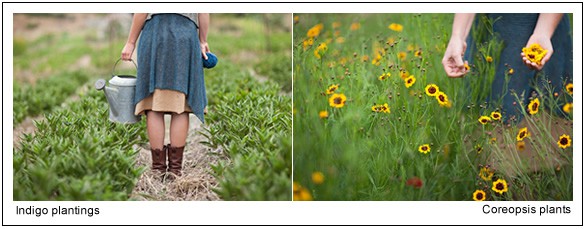

We continually surprised ourselves with our ability to devise local solutions when faced with challenges. In response to the toxicity of coal-tar-based synthetic dyes and a desire to grow our own colors, an indigo and coreopsis farm was started. These two species provided us with blue and orange. Other colors were sourced from native, wild, and naturalized plant species that were found throughout the gardens and ranches within the region.

The Future

The Fibershed project has now evolved into a 501c3 non-profit organization to support the continued development and growth of the bioregional textile network. The primary focus is to stabilize a local economy to support the continued farming and artisanal work of the Fibershed community. The project has begun an online marketplace that offers customers everything from raw fibers to finished goods. The marketplace is a venue for individual farmers to offer their fiber, yarns, and batting directly to the community. It also gives artisans the ability to source raw materials with ease. Finished products illuminate the collaborations within the local community.As the regional economy grows we will have greater opportunity to develop our renewable energy powered supply chain. We envision being able to offer head-to-toe clothing options, making use of all the raw fibers—from the highest quality angora, to those wools that are currently considered by-products, and bringing in well-engineered solar-powered milling equipment to support us in making the most refined and highest quality goods available. We foresee heirloom, homegrown textiles that are made to last a lifetime, that derive from a thriving system of farms, ranches, and human-scale regionally based manufacturing systems that benefit people and planet for generations to come.

We at Fibershed hope our model can serve as a guide for other communities interested in increasing their resiliency and self-sufficiency. We also hope it offers inspiration that sustainable, local solutions for almost any product or service can be successfully developed by those willing to dream big and put in the sweat work to make it a reality. The future is truly in our hands and will be what we make of it.

Resources:

Fibershed Website - http://www.fibershed.com/

Fibershed Marketplace - http://www.fibershed.bigcartel.com/

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/fibershed-a-case-study-in-sourcing-textiles-locally-2/