Every now and again, it’s good to take stock of the Great Global Reflation that has been marching higher (with a few stumbles and scares) since early 2009, over eight years ago.

Is this Great Reflation running out of steam, or is it poised for yet another leg higher? Which is more likely?

Keynesianism Vs The Real World

Let’s start by reviewing the systemic contexts of the economy.

This Great Reflation is embedded in two basic contexts:

- The dominant socio-economic structures since around 1500 AD are profit-maximizing capital (“the market”) and nation-states (“the government”).

- The dominant economic theory for the past 80 years is Keynesianism, i.e. the notion that the state and central bank must aggressively manage private-sector consumption (demand) and lending via centrally planned and funded fiscal and monetary stimulus during downturns (recessions/depressions).

Simply put, the conventional view holds that there are two (and only two) solutions for whatever ails the economy: the market (profit-maximizing capital) or the government (nation-states and their central banks). Proponents of each blame all economic and social ills on the other one.

In the real world, the vast majority of Earth’s inhabitants operate in economies with both market and state-controlled dynamics in varying degrees.

The Keynesian world-view is doggedly simplistic. The economy is based on aggregate demand for more goods and services. People want more stuff and services, and as long as they have the means to buy more stuff and services, they will avidly do so (this urge is known as animal spirits).

The greatest single invention of all time in the Keynesian universe is credit, because credit enables people to borrow from their future earnings to consume more in the present. Credit thus expands aggregate demand for more goods and services, which is the whole purpose of existence in this world-view: buy more stuff.

But credit, aggregate demand for more stuff and animal spirits make for a volatile cocktail. The euphoria of those making scads of profit lending money to those euphorically buying more stuff with credit leads to standards of financial prudence being loosened. In effect, lenders and borrowers start seeing opportunities for profit and more consumption through the distorted lens of vodka goggles.

Lenders reckon that even marginal borrowers will earn more in the future and therefore are good credit risks, and borrowers reckon they’ll make more in the future (i.e. the house they just bought to flip will greatly increase their wealth), and so borrowing enormous sums is really an excellent idea—why not make more money/enjoy life more now?

But the real world isn’t actually changed by vodka goggles, and so marginal borrowers default on the loans they should never have been issued, and lenders start losing scads of money as the value of the collateral supporting the defaulted loans (used cars, swampland, McMansions, etc.) falls.

Oh dear! The hangover of credit expansion is brutal, as lenders go bankrupt, wiping out their owners, and borrowers go bankrupt as they are unable to make their payments or sell the collateral to pay off the loan.

Just as credit expansion feeds on itself—everybody’s making a fortune buying and flipping houses, let’s go buy a house or two on credit—the hangover is also self-reinforcing: the value of collateral falling pushes more marginal borrowers into insolvency, and the lenders who made the loans are pushed into insolvency as defaults increase and collateral melts like ice in Death Valley.

In the Keynesian universe, this self-reinforcing contraction of imprudent credit and widespread losses of speculative wealth are Bad Things. Very Bad Things. Important, Powerful People tend to own issuers of credit (banks), and losses are not something they signed up for.

If all the Little People stop borrowing more money, the Powerful Owners of the credit-issuing machines (banks) can no longer reap enormous profits from issuing more credit, and that is a Very Bad Thing.

As a nasty side-effect of the credit hangover, businesses that depended on people borrowing more money to buy more stuff also shrink, and this contraction is also self-reinforcing: as sales decline, businesses must cut costs to stay solvent, which means laying off employees, abandoning under-utilized offices, closing factories, etc.

The euphoria of credit expansion turns to painful contraction. Nobody’s happy in the hangover phase, and people naturally cry out, Somebody do something to stop the pain!

The Keynesian answer is simple: the government should borrow and spend lots of money to replace all the money that the private sector is no longer borrowing and spending, and the central bank should lower interest rates and create a lot of new money that private banks can borrow cheaply to loan out to private-sector businesses and consumers.

In the simplistic Keynesian Universe, the credit contraction is like a temporary drought: all the government and central bank have to do to fix the drought is release a flood of new money onto the parched landscape of the credit-starved private sector, and aggregate demand and new loans will blossom like spring flowers.

Horray for central states and banks! Given the power to borrow (or create out of thin air) as much money as they need to flood the private sector with fresh money and credit, the drought ends, animal spirits are revived, people get to buy more stuff by promising to give their future earnings to banks and Powerful Owners of banks are once again earning great gobs of cash from lending to the Little People (i.e. borrowers in danger of becoming debt-serfs, whose earnings go largely to service their debts).

In the crayon-coloring book of Keynesian ideology, this is The Way the Universe Works. The problem is always a temporary drought of aggregate demand caused by a temporary drought of private-sector credit, and the solution is always a state-central-bank issued flood of money and credit: the government borrows and spends more money to replace declining private spending, and central banks make it cheaper and easier for private banks to issue new loans to enterprises and Little People.

That this coloring-book ideology no longer describes the problem or solution is incomprehensible to the Keynesians. That neither “the market” nor “the government” can solve the current set of problems is equally incomprehensible—not just to Keynesians, but to everyone who unthinkingly accepted that the market and/or the state can always fix whatever problems arise.

Oops! The Flood of Money and Credit Didn’t Fix the Economy

The post-credit/asset bubble crashes in 2000 and 2008 and the state/central-bank responses--fiscal and monetary stimulus, a.k.a. flood the land with borrowed money—seemed to confirm the Keynesian world-view: marginal borrowers, lenders and collateral all went south and the stimulus restored animal spirits, which promptly inflated a new credit/asset bubble.

But this time around, the drought never ended, no matter how much money was poured into the economy, and the earnings of borrowers stagnated or declined. (Recall that debt is borrowed from future earnings; if earnings decline, it becomes much more difficult to service existing debt, much less borrow more.)

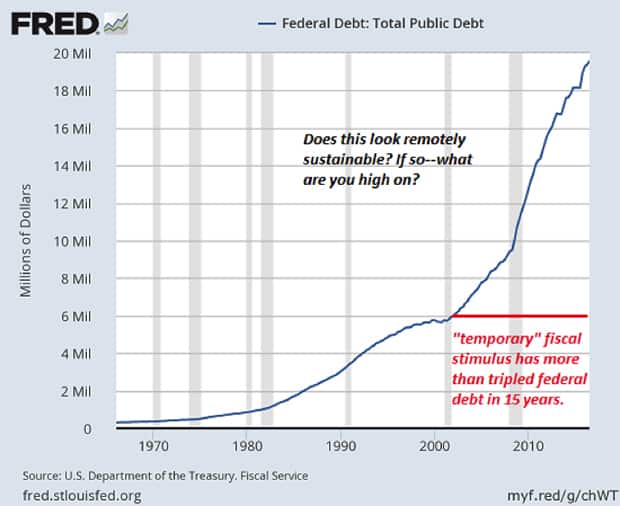

Federal debt has more than doubled just since 2009 (and tripled since 2001) as the government flooded the land with fiscal stimulus:

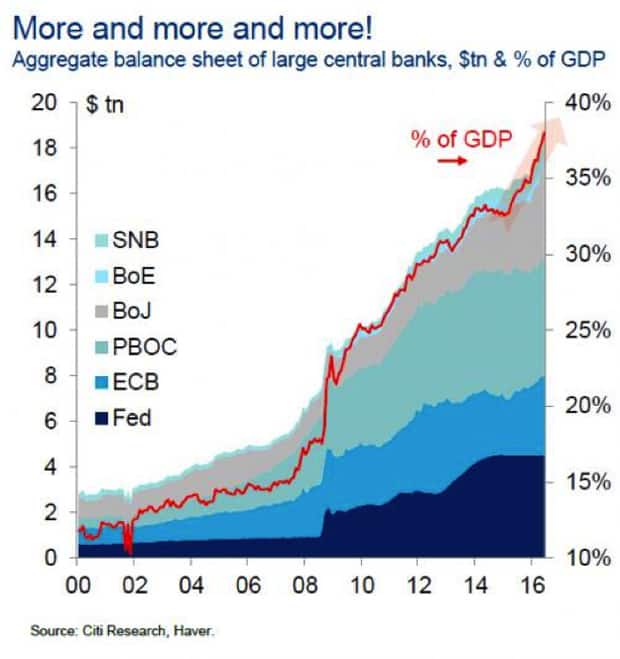

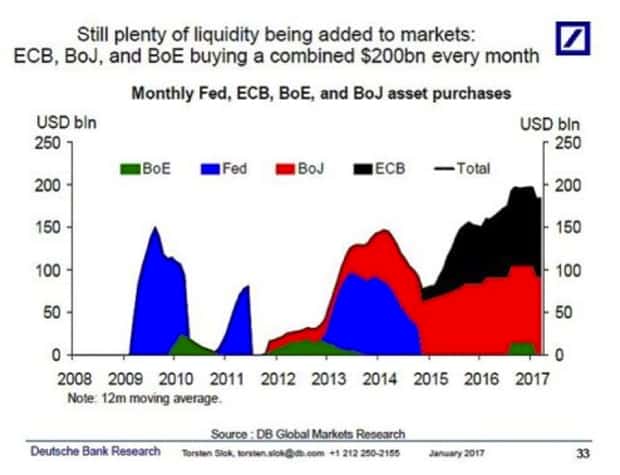

Central banks have flooded the global economy with trillions of dollars, euros, yen and yuan, and continue to do so to the tune of $200 billion per month:

Central banks have dumped over $1 trillion in new monetary stimulus in the first four months of 2017—eight years after the “emergency” stimulus began:

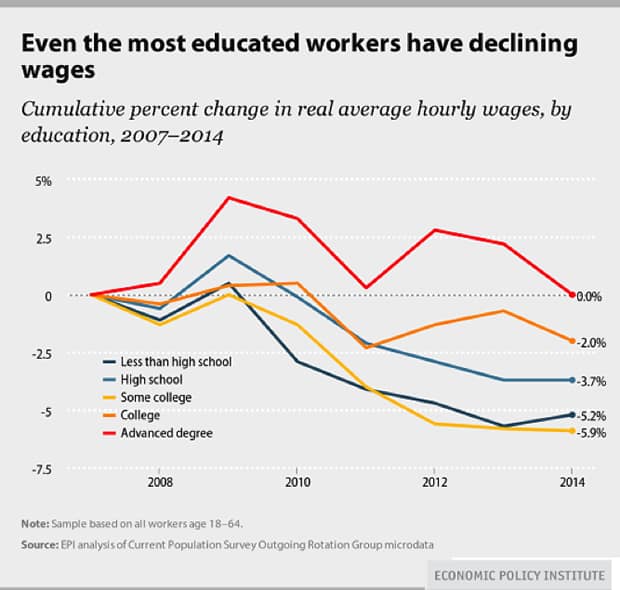

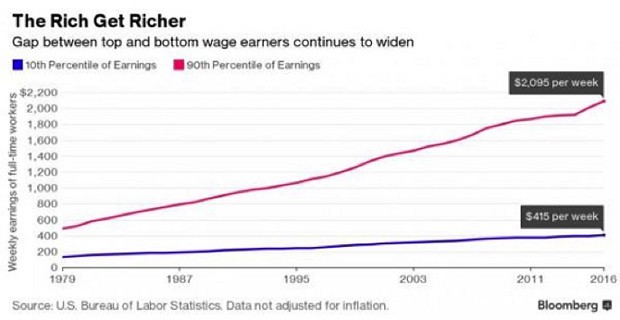

Meanwhile, wages are stagnant or declining for the vast majority of wage-earners—even the highly educated:

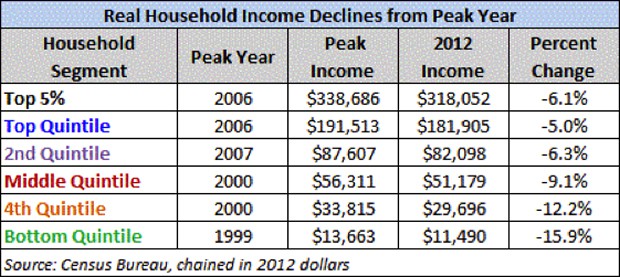

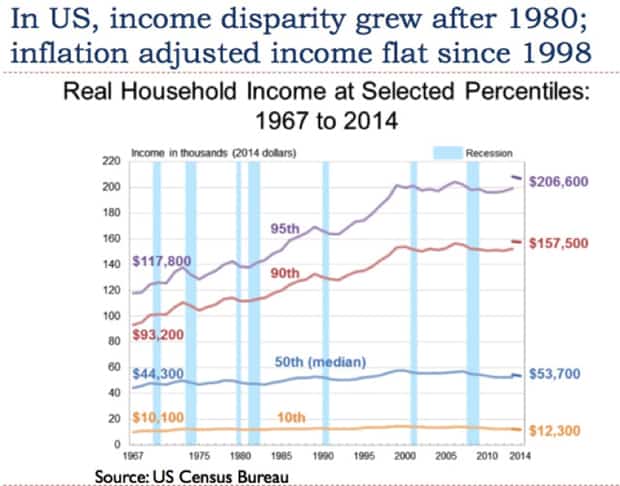

Household income has fallen across the board:

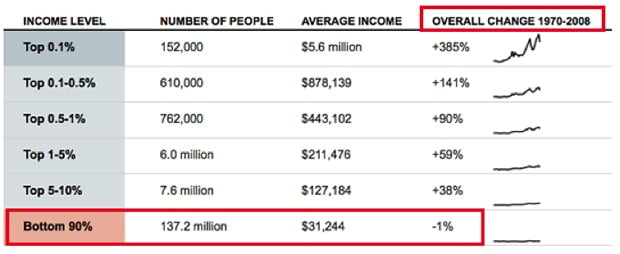

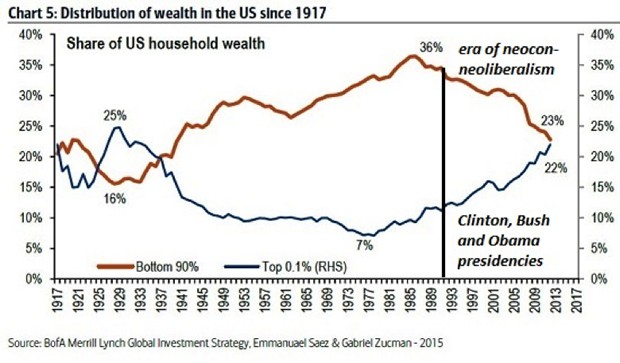

Stagnating incomes is not a new issue for the bottom 90%; it’s a structural reality going back four decades:

Clearly, fiscal and monetary stimulus policies that were supposed to be temporary are now permanent. That isn’t what was supposed to happen.

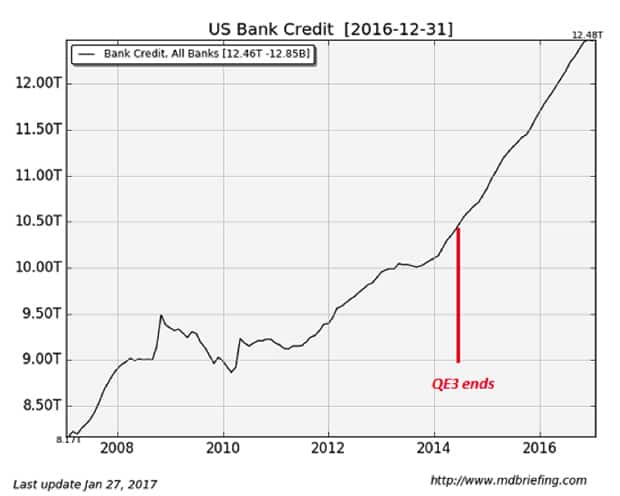

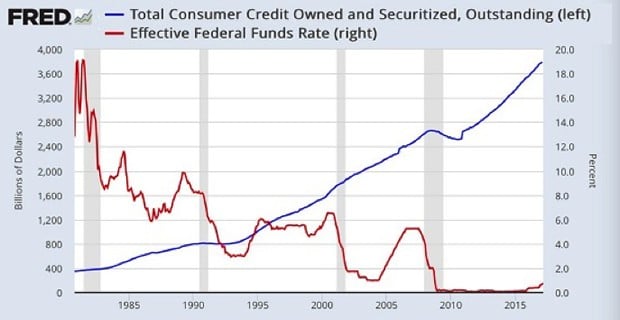

Earnings were supposed to rise once private-sector credit and consumption returned to expansion. As we see here, bank credit and consumer credit have surged higher, but the incomes of the bottom 90% have gone nowhere.

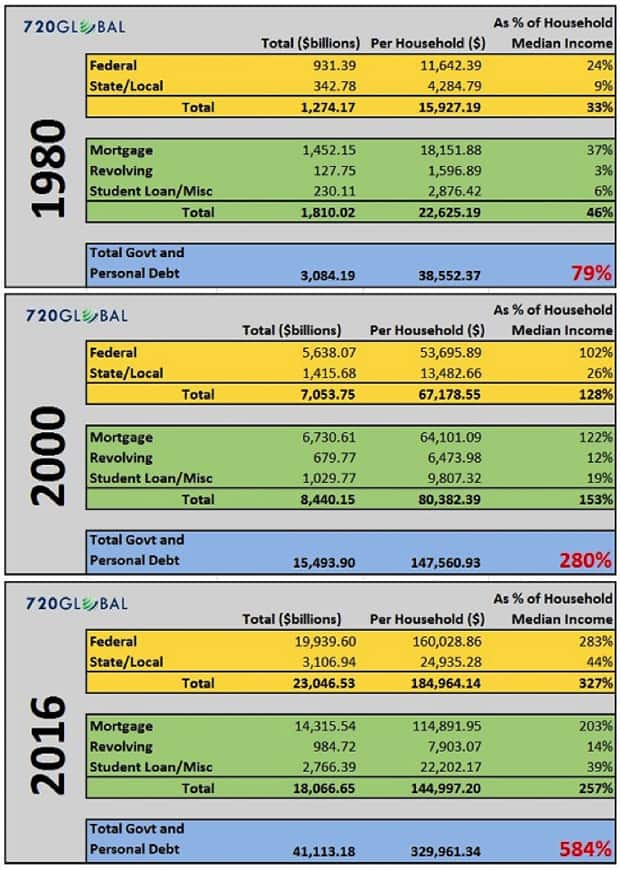

Meanwhile, total debt—government, corporate and household—has rocketed higher, more than doubling from 280% of GDP in 2000 to 584% of GDP in 2016:

As if these weren’t bad enough, wealth and income inequality have soared during the era of permanent fiscal-monetary stimulus:

In sum: nothing has worked as the Keynesians expected. Instead, state/central bank measures that were supposed to be temporary are now permanent, and the expansion of private-sector debt has failed to “trickle down” to earnings.

The Keynesian solution—borrowing from future earnings to “bring consumption forward”—has expanded consumption at the cost of enormous increases in debt throughout the economy, which has exacerbated income-wealth inequality and declining real incomes.

Can we finally admit that eight years of following the Keynesian coloring-book plan have not just failed, but failed spectacularly, and not just failed spectacularly, but made the economy even more vulnerable and fragile, as more and more future income must be devoted to service the skyrocketing debts?

Isn’t it obvious that there are deeply structural problems in the economy that inflating yet another cred/asset bubble won’t fix?

Clearly, the real-world economy does not function like the simplistic Keynesian coloring-book model.

What Comes Next: Contraction

Given the extraordinary failure of both Keynesian stimulus and private-sector credit growth to create a self-sustaining cycle of expansion whose benefits flow to the entire workforce rather than to the top few percent, what can we expect going forward? Can we just keep doubling and tripling the economy’s debt load every few years? What if household incomes continue declining? Are these trends sustainable?

In the near-term, is this Great Reflation running out of steam, or is it poised for yet another leg higher? Which is more likely?

In Part 2: Prepare For The Great Global Contraction, we detail why the economy’s structural problems languish unaddressed, and how the inflating of yet another speculative credit-asset bubble has not fixed these problems. Instead, the current credit-asset bubble has dramatically increased the fragility of the economy by diverting capital from potentially productive investments to unproductive speculative gambles, and by increasing the unproductive burdens of soaring debt.

When the Great Reflation does finally roll over, there will be plenty of time to ponder what investments might do well—but only those who exit well before the rollover will have the cash to take advantage of the opportunities.

Click here to read the report (free executive summary, enrollment required for full access)

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/how-long-can-the-great-global-reflation-continue/