The Allium family contains some of the easiest plants to grow in a raised bed, row, or even a container. At the same time, there are a few basic things you need to be aware of to have success and grow a bountiful crop that will store well. Although it may not be the right time of year to plant some of the delicious alliums I am going to talk about, it is essential that you consider what you want to grow in the future and buy your seed or starts as soon as a company will accept a pre order. Many suppliers of garlic and shallot start to sell out before it is time to plant. The economic time we are facing and worker shortages have made it even more critical to pre-order now for fall planting.

Reasons To Grow Alliums

- Easy to grow in practically any climate

- Flavorful

- Very disease and pest-resistant. Simple to grow organically.

- Its simple to save seeds and starts

- Allows you to use a variety of alliums in your everyday cooking affordably. No paying $3-$8 per lbs for shallots, garlic, or leeks!

Bunch Onions

[caption id="attachment_658726" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Photo Courtesy of Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds[/caption]If you are tired of paying $2 for a small bundle of bunch onions or “scallions,” then you should consider growing them at home. Bunch onions are perhaps the easiest onion to grow, and once planted, you can keep a bed or container of them going indefinitely. Using a cold frame or row cover, you can harvest bunch onions year-round, even in fairly cold climates. If grown in a container, bunch onions will thrive indoors year-round, making them a good choice for apartment dwellers.

Bunch onions are easy to grow from seeds, or you can buy some organic bunch onions at the store and save the white bottom with the roots and replant those to get started a little faster.

Sew seeds when the ground is workable in the Spring. You will probably need to thin them out over time. You can, of course, transplant them in a way so that spacing is better.

We often clip the tops of bunch onions and leave the bulbs to regrow. This seems to work well for us.

Shallots

[caption id="attachment_658728" align="alignnone" width="1280"] Curing shallots[/caption]Although there are plenty of shallots grown in the Pacific Northwest and parts of California, the majority of what you see in USA grocery stores are grown in Holland. They are very expensive for an onion. I fell in love with cooking with shallots when I was in my 20s and trying out new recipes, particularly some of those that Martha Stewart put in her magazine.

Years ago, we learned the hard way that growing shallots requires finding a variety suited to your climate. The first time we grew shallots, we planted the standard red shallots you find at the grocery store. They never bulbed outright. In fact, they stayed small and hard. A few rotted, too, because we did not understand that well-drained soil is critical. You cannot water shallots like you do a lot of garden crops such as tomatoes.

Eventually, we decided to give it another try. I ordered 10 lbs of French Red Shallot starts from Peaceful Valley this year. We had a great harvest this year, as you can see from the pictures! We planted them in a well-drained spot, and my husband Matt was careful not to overwater them.

No more paying $3-$4 for two small shallots at the grocery store. It always felt a little absurd buying an onion that had to be shipped all the way across the Atlantic too.

Shallots are planted on a 6" x 6" grid. Do not be tempted to put them closer together. You need all that space to allow for the massive multiplication of bulbs that you get. As far as depth goes, you need to dig down enough that you can cover the shallot start with about 1/2" of soil. Make sure you are putting the shallot in the ground with the top facing up. You may have to come back and recover them a little if you get a heavy rain that washes soil away.

Garlic

[caption id="attachment_658729" align="alignnone" width="550"] Creme De La Rasa Garlic. Photo Courtesy of Crater Lake Farm. This is the variety my husband and I ordered. It will be ready to harvest in a few weeks. Crater Lake Farm is already taking orders for seed garlic to be delivered this fall if you want to get a head start and make sure you get the variety that you want.[/caption]

This year was not our first time growing garlic. I will warn you that purchasing quality seed garlic costs a lot. 5 lbs of quality seed garlic will allow you to harvest around 300 heads of very high-quality large garlic bulbs. The cost for that 5 lbs is around $120 with shipping. While that sounds high, you should remember that it is a one-time cost as long as you successfully grow some garlic the following year. You can save your seed year after year. While you can plant garlic from the grocery store, the results are often not great. I recommend spending the money on high-quality seed garlic because you can choose a variety that is best suited to your tastes and your climate. My husband and I got tired of all the tiny little cloves that you have to peel if you get garlic at the grocery store. The variety we chose to grow provides 6-8 large cloves, which reduces prep time by a lot. Growers that sell seed garlic choose their best garlic heads to sell, which is part of what you are paying for. When you choose your bulbs to save for seed the next year, you need to make sure to save some of your best too. These practices will make it possible to keep growing quality garlic year after year.

In North America, garlic is typically planted in very late fall or early winter. I am in western North Carolina, and we have found that right after Thanksgiving or the first week of December works well for us. I advise checking to see what is best for your specific region since planting times may vary by a month or two.

To plant regular garlic (not Elephant Garlic), you need to dig down around 2 inches. Loosening soil deeper down can help plants get established faster. Place a single clove in the hole. Space garlic cloves 4 inches apart. You can plant in triple rows on a 4" x 4" or 4" 6" grid. How big of a grid you plant is up to you, really, but you want to be able to reach your garlic to keep it weeded without overstretching. A raised bed where you can walk around all sides can be nice for garlic.

Tips for Garlic Success

- Keep it well weeded. This is not particularly hard to do since, a lot of the time, it is in the ground is during the cooler months of the year when weeds are not too bad.

- Water regularly.

- Plant in well-drained soil. If soil doesn't drain well, you risk rot. Using peat moss, sand, or vermiculite can help lighten heavy soils.

- Fertilize as needed. We have good soil, but we still fertilize our garlic a couple of times.

Globe Onions

With globe onions, you want to make sure that you are planting varieties that are suited to the number of daylight hours you have during the main growing season. This is easy to do by looking at a simple map. You may be able to grow many different types of onions if you live in a place that has very long days in the summer. If you plant onions that require 16 hours of daylight in a region that gets only 12, then you will be very disappointed in the size of the onion you harvest at the end of the season. In extreme cases, they may not bulb much at all.

Short Day- Bulb when day length reaches 10-12 hours

Indeterminate-Bulb when day length reaches 12-14 hours

Long Day -Bulb when day length reaches 14-16 hours

Here is a link to a handy map that can help you determine what type of onion is best for your area.

Egyptian Walking Onions or Tree Onions

These onions are interesting. They produce a small bulb similar to a shallot. The big difference is that they produce bulbs on top of the plant. At some point, these bulbs fall over and basically, implant themselves in the soil, hence the name “Walking Onion.” These are a nice choice for those that want an onion that will come back year after year. You can also harvest top bulbs and sell them to others for a good price so they can get started growing Egyptian Walking Onions.

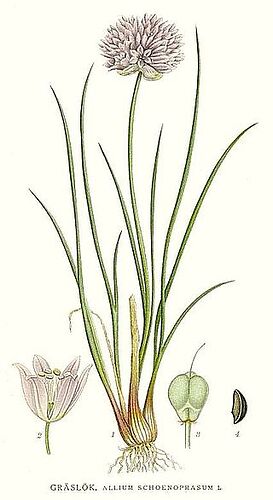

Chives

Chives grow wild in my area for part of the year. They are super easy to harvest and dry in a dehydrator. You can dice them up with a pair of scissors and store them with a moisture absorber for use year-round. No more buying those expensive little jars.

If you want fresh chives year-round, you can easily grow them in a container on a window sill in the winter. They grow fast, so you don’t need to take up a ton of growing space inside or out to keep a bountiful supply on hand.

If you have wild chives growing around you, then you can dig up a clump or two and transplant to your garden or container. They will spread a lot over time if you don’t control them well.

Domestic Leeks

[caption id="attachment_658734" align="alignright" width="300"] Photo of Giant Musselburgh Leeks Courtesy of Territorial Seed Co.[/caption]Leeks are a great high-dollar onion to grow. They winter over well in moderately cold climates without any special treatment. In frigid temperatures, a little straw or other covering would go a long way.

The last time I was in a grocery store, leeks were around $3-$4 for a bundle of 3 or 4. I am guessing that the bundles weigh around a pound.

My husband Matt and I grow Giant Musselburgh Leeks and sometimes American Flag Leeks. Both do well, but I have to say that the Giant Musselburgh seem to grow to a little larger and perhaps winter over a little better.

Leeks are grown a lot like bunch onions. You sow a row or raised bed and thin them out or break them up and space them out better if desired. You can eat leeks at any size. You can cut some greens off the top and leave the bulb in the ground, and it will grow back. If you pull up full-size leeks, consider keeping the very bottom with the roots and replanting wherever you desire.

Leeks are easy to slice up and dry in a dehydrator for use in whatever recipe you like. Leeks are excellent in soups and stews and can be used to substitute in any recipe that calls for scallions or green onions.

To grow leeks you simply sow them in row, covering lightly with soil. You will need to thin them out a bit after they sprout. We sometimes start them in a container or bed and then transplant them into rows or rearrange them in a bed so that they are spaced 3 inches apart.

Ramps or Wild Leeks

In the mountains of Appalachia, we look forward to ramp season. It means that warm weather is close and that we will start to get some food from nature and spring gardens!

Ramps are a small wild leek that you can naturalize on your place or encourage to spread if you discover you have a patch on your land.

If you don’t have any ramps growing on your property but live where they grow wild, I advise buying some from a produce stand. You can eat the tops and plant the bulbs if you must, but I would buy a few extra bundles and plant them in a spot that stays shaded and damp for best results. You will have to create these conditions if you don’t have a natural spot. We have some wet and shady spots near our creek that work well for this. Ramps will spread over time, but they will spread even faster if you clip the tops off and leave the bulb in the ground.

These are pretty smelly onions to cook and consume. When my Dad was a kid in the 50s, kids would be forced to sit outside the classroom in the hallway sometimes if they had eaten too many at home and come to school smelling like them.

We have never minded the smell too much ourselves. I guess it depends on how sensitive you are when it comes to scents.

If you forage for ramps, make sure it is in an area where you are allowed to do so and never take all of them. Leaving some ramps means that there will be more there next year. Taking all of them means you have probably eliminated that spot entirely.

Sources For Onion, Garlic, and Shallot Starts

Dixondale FarmsPeaceful Valley (Source for shallot sets featured in this article)

Crater Lake Farm (Produces a variety of high-quality seed garlic.)

Books For Onion and Garlic Growers

Growing Great Garlic: The Definitive Guide for Organic Gardeners and Small FarmersAll the Onions: Storey’s Country Wisdom Bulletin

The Vegetable Gardener’s Bible

Conclusion

Onions, garlic, and shallots are an easy-to-grow choice for any home gardener. The main things to remember for onion success include:- Determining what type of onion is best for the number of daylight hours you received.

- Provide adequate water, fertilizer, and drainage.

- Make sure you are clear on when to harvest and how to cure and dry your onions, garlic, and shallots, so they keep well.

Do you have experience growing alliums to share? Join the conversation below!

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/how-to-grow-onions-garlic-and-shallots/