After 30 years of torrid expansion, perhaps the single most consequential factor in China’s economy is how much of it is a “black box”: a system with visible inputs and outputs whose internal workings are opaque.

There are number of reasons for this lack of transparency:

- Official statistics reflect what officials want to project, not the unfiltered data.

- Policy decisions are made behind closed doors by a handful of leaders.

- There is little institutional history of transparency.

- Many important statistics are self-reported and prone to distortion.

- Large sectors of the economy are informal and difficult if not impossible to measure accurately.

- Endemic corruption distorts critical economic yardsticks.

- There is little historical precedent to guide policy makers and individual investors.

None of these is unique to China, of course, with the possible exception of #7: few nations in history (if any) have experienced an equivalent boom in infrastructure, credit, housing and wealth in such a short span of time.

Saving Face By Editing Data

As anyone who has lived and worked in Asia can attest, public perception (i.e. "face") is of paramount concern. There is tremendous pressure to put a positive spin on everything in the public sphere. Negative publicity causes not just the individual to lose face, but his boss, agency, company and family may also be tarnished.

For this reason, reporting potentially negative numbers accurately may put careers and hopes for advancement at risk.

This accretion of fear of reprisal/disapproval builds as it moves up the pyramid of command. This process can lead to tragic absurdities being taken as truth. In one famous example in Mao-era China, officials ordered rice planted in thick abundance along a particular stretch of road, so that when Chairman Mao was driven along this roadway, he would see evidence of a spectacular rice harvest.

In reality, China was in the grip of a horrific famine resulting from disastrous state policies (The Great Leap Forward). But since everyone feared the consequences of telling Mao his policies were starving millions of Chinese people, the fields along the highway was planted to mask the unwelcome reality.

Even the most honest reports reflect the biases of those summarizing feedback for their superiors. As a result, when the feedback finally reaches the top leadership, it may be inaccurate or misleading in ways that are difficult to detect.

The Dangers Of Opaque Leadership Decisions

All leaders have their own biases and experiential limits, and left unchecked by accurate feedback and honest dissent, these have the potential to generate disastrous decisions.

Perhaps the top leadership in China is soliciting honest dissent, but without a vigorously free media and multiple unedited feedback loops, this is unlikely for systemic reasons.

Most people—leaders and followers alike—seek to confirm their own views (i.e. confirmation bias). A system in which key decisions are not aired publicly and the trustworthiness of the data being considered behind closed doors is also unknown is a system designed to reinforce confirmation bias and yes-men.

In this environment, destructive policies may be supported by the chain of command despite the consequences.

Lack Of Institutional History of Transparency

Institutions with a long history of independence and a policy of priding transparency have the potential to counter the tendency of hierarchies to encourage confirmation bias and fudged feedback.

But China’s tumultuous history in the 20th century—invasion, foreign occupation, civil war, revolution, mass famines, the Cultural Revolution’s mass disruptions and purges, the end of Mao’s Gang of Four and Deng Xiaoping’s “to get rich is glorious” reforms—has not been conducive to the establishment of independent institutions.

Developing the independence of institutions in the midst of such unprecedented political, social and economic turmoil is a long-term work in progress. Though no comparison is entirely analogous, we can look at the first equally tumultuous 30 years of the American Republic (1790 – 1820) and the French Republic (1789-1819) for historical examples of the difficulties in establishing enduringly independent institutions.

Self-Reported Statistics

Self-reported data plays a significant role in any economic snapshot that measures sentiment and expectations. But when it comes to income, outstanding loans and other data, there’s no substitute for accurate numbers.

As a general rule, the larger the informal cash economy and the greater the leeway and the incentives to under-report, the lower the quality of self-reported statistics.

Take income as an example. In the U.S., the vast majority of non-cash income is reported directly to the tax authorities: wages, 1099s, sales of securities, etc. The leeway to fudge income is low, which pushes the incentives to fudge onto the expense/deduction side of the ledger. For this reason, IRS income data is more trustworthy than self-reported measures of income and employment.

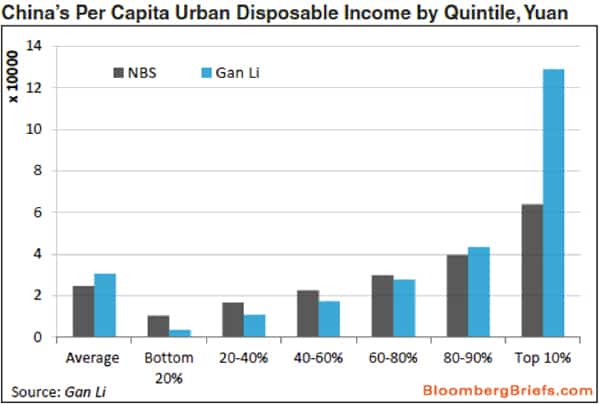

Consider this chart of household income in China. A survey of households found incomes were much higher than the officially collated numbers. In the case of the top earners, the difference was significant enough to skew a variety of key numbers such as household income as a percentage of GDP.

(Source)

The differences between official data and data collected by surveys is troubling for a number of reasons. Given the incentives to under-report (to avoid paying higher taxes), why should we trust the accuracy of self-reported income? Who’s to say that wealthy households don’t habitually under-report their true income even to surveys?

Given the ubiquity of the informal economy and shadow banking system in China, official data cannot accurately reflect peer-to-peer lending, private loans outstanding and many other data points that are critical to understanding income, risk and credit flows.

The Informal Economy & Shadow Banking

These discrepancies between actual debt and what’s reported could have monumental consequences should expansion turn to contraction and debts become uncollectible.

It’s been estimated that a third of all Chinese households engage in informal lending to friends and family, as well as to enterprises that pay high rates of interest due to the risky nature of their investments.

Interest can run as high as 34% -- loan-shark rates.

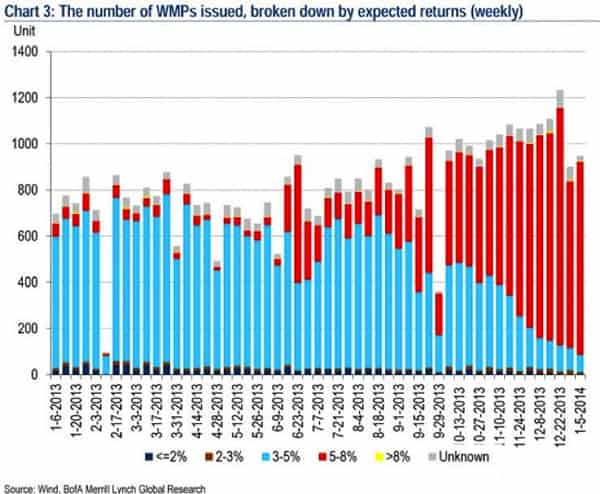

Even the slices of the credit/investment sector that are reported—for example, Wealth Management Products (WMPs)—are more Wild West than staid banking. WMPs are managed off-balance sheet and don’t require any reserves:

“Legally WMPs are not deposits. They are investment products that are managed ‘off-balance-sheet’ by banks, and there is little transparency about where the funds are going,” said Stephen Green, head of Greater China research at Standard Chartered in Hong Kong, in a note.

According to Green, the funds from different WMP products are often mixed and deployed to finance a broad pool of assets that more often than not fall into the sectors of the economy that regulators have attempted to fence off from normal bank lending (real estate, local government infrastructure, etc.), partly because these sectors are deemed to be particularly risky. In addition, the banks hold neither reserves of WMP deposits nor capital against the assets.

(Source)

In other words, transparency is low while risk is unknown but possibly high. This volatile mix of opacity and risk is the perfect recipe for cascading defaults and catastrophic losses.

Endemic Corruption Distorts Data

In China, as in many developing economies, problems such as permit applications, tax bills or development rights are solved by greasing the skids of officialdom. Just received a big tax bill? Maybe a friendly tax official can help reduce the tax in return for promises of favors and an envelope of cash.

While the central government is cracking down on highly visible corruption, the system of buying privileges with influence, favors and cash is too deeply entrenched to be eliminated in a few months or years by high-level policies.

As with all the factors listed here, the impact of corruption is difficult to assess -- and that’s what makes China’s economy such a black box: if what’s known is untrustworthy, and what’s not known is potentially destabilizing, then how reliable is any projection?

Few Historical Precedents to Guide Policy Makers and Individuals

In the U.S., analysts and policy makers can draw upon a long history of economic policies and debate their applicability to the present. Rising income disparity, for example, is often compared to the Gilded Age of the late 19th century. The financial crisis of 2008 is often viewed as an analog of the 1929 crash that triggered the Great Depression.

China’s recorded history stretches back thousands of years, but in terms of applicable financial and economic parallels to the current economy, there is no precedent. China’s leadership is truly in uncharted waters. This in itself heightens the risk of miscalculation and basing policies on faulty premises.

In Part 2: Why China Is Extremely Vulnerable Now, we zero in on China’s real estate bubble, and the outsized risks it poses to China’s economy -- and the world.

As the housing bubble bursts, alongside the trillions of losses already experienced in the Chinese stock market, the flood of capital from China into world assets is going to be substantially compromised. Asset prices are set at the margin: what the highest buyer is willing to pay. For many years now, the world has become accustomed to China's dependable willingness to pay well in excess of everyone else. When China is no longer the highest buyer, how far will prices need to fall in order to match the next highest buyer's ability to pay?

Click here to read Part 2 of this report (free executive summary, enrollment required for full access)

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/is-chinas-black-box-economy-about-to-come-apart/