Few modern economists would, for example, monitor the behaviour of Procter and Gamble, assemble data on the market for steel, or observe the behaviour of traders. The modern economist is the clinician with no patients, the engineer with no projects. ~ John Kay, from The Map is Not the Territory: An Essay on the State of Economics, October 2011

I’m not quite sure what a depression is. ~ Martin Feldstein, in an interview with Kelly Evans of the Wall Street Journal, October 2011

A Failure To See the Obvious

Prior to 2008 it was generally understood that the profession hardly merited its claims of its own predictive utility. So the failure to assign enough risk to such a crisis as befell the developed world in 2008 was, frankly, no surprise. But in the aftermath of the crisis, economics, in its professional form, has revealed itself to be damagingly disconnected from observable reality.

A glaring example of this is how it cannot come to any agreement as to how the debt crisis occurred, and accordingly remains quite confused in its proffered solutions.

Mostly the profession remains curiously naive about the nature of debt, an understanding of which is more critical than ever as the developed world enters a 'slow' to 'no-growth' phase of its history. Indeed, many of the papers, interviews, and op-eds from central bankers and economists in the face of our present-day sovereign debt crisis are little more than an eerie restatement of the discussions which took place about private-sector debt from 2006-2008.

For a profession tasked with the analysis of dynamic systems, modern economics can be ploddingly linear. And for a profession supposedly guided by math, the descent into "sociology lite" is all too routine. One of the more consistent errors (or nervous tics, if you will) comes in the area of scale and proportion. A favorite and most astonishing example for me remains former Dallas Fed President Bob McTeer’s explanation of the cause of the 2008 crisis. Writing in his blog at the end of 2009, McTeer set out to defend the US Federal Reserve for its role in the catastrophe:

It is taken as given these days that the Fed created the housing bubble. If this is true, then it must follow that the Fed is responsible for the bursting housing bubble, the ensuing financial crisis and subsequent recession. But, as I recall, the Fed did not create the housing bubble. It was the collateralized subprime loans, not a reversal of home prices, that caused the problems. Maybe there were too many loans, but, if so many had not been bad loans, air could have come out of the bubble without devastation...Subprime loans triggered the crisis and recession. Other things like too much debt and leverage made the problem worse, but didn’t cause it.

Let’s stipulate that the issue of causality can almost always broaden out into legitimate disagreement. But Mr. McTeer’s claim here is so grossly disproportionate to the total size of the credit bubble, which was not limited to housing, that one is compelled to ask if Mr. McTeer actually understands the system over which the Federal Reserve presides. This blind spot towards debt growth, and in particular the rate of debt growth, counts as one of the more curious revelations to emerge from the crisis. Indeed, while the crisis finally produced a broader appreciation by the public of debt dynamics, it also produced a clearer portrait of the economic profession’s intractable position towards debt. In short, they “don’t see it.”

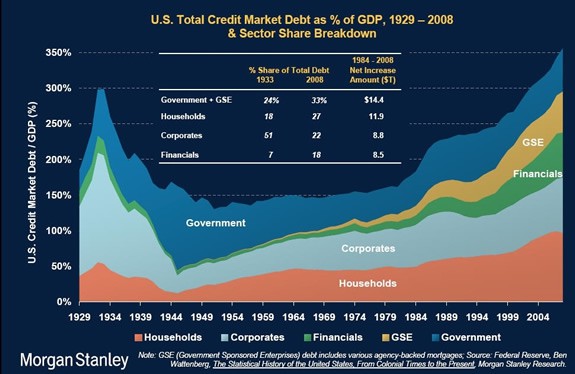

And, here’s what they don’t see. The following chart is composed of total debt growth in the US economy from 1929 and helpfully covers the period through 2008, compared as percentage of GDP. As you can see, the rate of debt growth starting after 1999 should have been on the radar of economists and central banks. Especially the Fed. The 1985-1998 period was relatively slow by comparison. But starting in 1999, total US Credit Market Debt to GDP exploded higher, from 250% to 350%.

Let’s rework the claim of McTeer, as follows: Subprime loans represented too small a portion of total credit to have either triggered or caused the crisis and recession. When growth slowed, the unsustainable amount of debt and leverage in the entire system was revealed, and thus made everything worse.

The cruel irony of McTeer’s faulty understanding is that the US economy would be powering out of recession right now, with typical 4-6% GDP growth, had the credit bubble been confined (contained!) to subprime. The relegation of the crisis’ beginnings or causes to subprime is now considered a kind of joke that flags a financially illiterate (or political) view. The US should have been so lucky as to have merely faced a subprime problem. Now there are 10.7 million US homes in negative equity. Twenty-five years of strong credit growth, a deflationary labor shock from the developing world, and a phase transition in energy prices set the stage, not for a post-war recession, but a depression. A meandering economic stagnation that can never produce a full recovery.

Founded On a Fallacy

Modern central banking came into existence, of course, during a secular growth phase in the developed world funded by cheap energy. Its task for most of the past 100 years has been to regulate growth -- not to manage decline. Much of the commentary you saw prior to 2008, such as Ben Bernanke’s sincere lack of concern about a US housing bubble (“I guess I don’t buy your premise. It’s a pretty unlikely possibility. We’ve never had a decline in house prices on a nationwide basis...”) is, of course, duplicated today as we confront a similar endgame in sovereign debt.

Economists in 2010, when the European crisis began, were sanguine. In the tête-à-tête between Hugh Hendry and Joseph Stiglitz last year, Stiglitz was adamant that debt service for Greece was no problem. More recently this summer, Jeffrey Sachs claimed at FT that there was a way out for Greece, by allowing the country to borrow at rates enjoyed by Germany. That may have seemed like the biggest catch to such a solution. I would submit, however, that the Sachs proposal contained a much larger uncertainty that is now the new blind spot common to the economics profession: the assumption of continued growth.

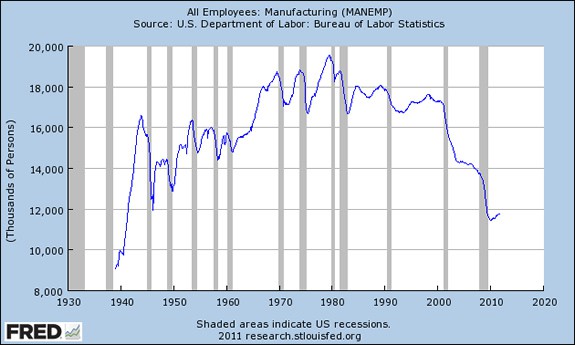

One of the more irritating personality traits of economics as a discipline is that it continually incorporates every trend into its growth model, and then identifies it as a good thing. The secular decline in US manufacturing jobs was deemed as such, as it “freed up” the populace to take service jobs. Interestingly, in our post-crisis economy, much of the selected regional strength in the US is now very much related to exports and a small resurgence in light manufacturing.

The Fed should have been paying closer attention to the multi-decade trend in US manufacturing employment. Instead, Alan Greenspan, a fan of Ayn Rand, believed the world operated in a magically offsetting series of harmonics, in which self-interest propagated though the financial system, producing a grand balance of risk. It is easy to understand how debt growth, cost inflation in health care and education, and the unsustainable bloat in the financial sector would flourish under such a paradigm. After all, “one person’s debt is just another person’s asset,” so what could possibly go wrong?

Worsening What They Don't Understand

When central bankers can’t initially understand why markets are rebelling against debt levels, they often turn to simplistic behavioral concepts. But a small dash of social psychology can be a dangerous thing when injected into monetary policy. Perhaps some moderate respect should be given now, many years after his tenure, to Alan Greenspan, who in testimony finally admitted that "the entire model he used to describe how the world worked, was wrong." In similar fashion, Ben Bernanke in his 2011 public testimony has admitted that the Fed “cannot print oil,” cannot solve problems without help from fiscal policy, and probably cannot force a faster economic recovery.

But one wonders how evolved the Fed chairman really is, given his public statements in 2009 that the financial crisis was merely in the fashion of a 19th-century panic. Instead of exponential growth in private credit, capricious monetary policy from the Fed itself, or the guns-and-butter fiscal policies of the government, Bernanke voiced publicly in his PBS TV performance and also at Jackson Hole that we had merely suffered a Bagehot-type panic. This may have been why he thought, as did many others, that a normal recovery would ensue.

Here is the key passage from the Jackson Hole conference on August 21, 2009, Reflections on a Year of Crisis (Interpreting the Crisis: Elements of a Classic Panic):

How should we interpret the extraordinary events of the past year, particularly the sharp intensification of the financial crisis in September and October? Certainly, fundamentals played a critical role in triggering those events. As I noted earlier, the economy was already in recession, and it had weakened further over the summer. The continuing dramatic decline in house prices and rising rates of foreclosure raised serious concerns about the values of mortgage-related assets, and thus about large potential losses at financial institutions. More broadly, investors remained distrustful of virtually all forms of private credit, especially structured credit products and other complex or opaque instruments.

At the same time, however, the events of September and October also exhibited some features of a classic panic, of the type described by Bagehot and many others. A panic is a generalized run by providers of short-term funding to a set of financial institutions, possibly resulting in the failure of one or more of those institutions. The historically most familiar type of panic, which involves runs on banks by retail depositors, has been made largely obsolete by deposit insurance or guarantees and the associated government supervision of banks. But a panic is possible in any situation in which longer-term, illiquid assets are financed by short-term, liquid liabilities, and in which suppliers of short-term funding either lose confidence in the borrower or become worried that other short-term lenders may lose confidence. Although, in a certain sense, a panic may be collectively irrational, it may be entirely rational at the individual level, as each market participant has a strong incentive to be among the first to the exit.

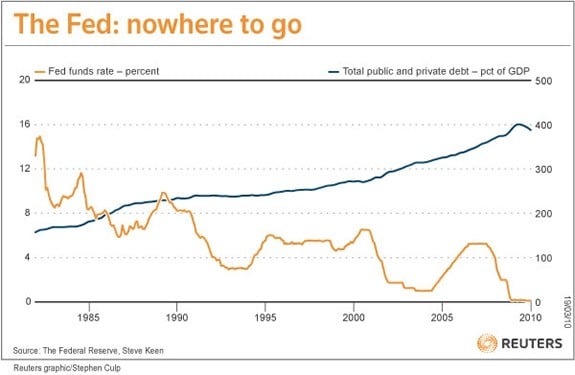

The Fed Chairman is using a technique here called hiding in plain sight, or perhaps secrecy by complexity. It is inarguable that a behavioral panic took place. But the aim was clear: to avoid the debt saturation in OECD/developed nations and the United States and the years of slow-to-no growth it was fated to impose. More broadly, the Fed had been “managing” the growth of debt in the US economy for over two decades. 2008 was the signal that the long, secular era of lowering interest rates to help the economy manage its debt levels had reached its endpoint.

One possible explanation for this blind-spot towards debt is that the economics profession is largely in service to the political class. Books, such as Reinhardt and Rogoff’s This Time is Different, which addresses the limits imposed by debt, are generally not in favor in the current era. Equally, the moral flavor to much of the right-leaning thinking on debt is also unsatisfying, as it also does not address debt-saturation so much as fiscal rectitude. What matters instead are the levels in both private-sector debt and public-sector debt that impose operational restraints. Total debt service as a proportion of income will always create a limit eventually among private sector borrowers. That is precisely what began to occur in the US and was the prima causa of the recession. However, the precise, problematic levels of debt for sovereign nations are trickier to identify.

The Tide Is Changing

Through a combination of confidence, debt service, actual economic flows, and the marketplace, however, 2012 is almost certainly the year that the present sovereign debt problems will be resolved, one way or another. Also, this week’s US dollar swap operation likely points towards one of the two macroeconomic endgame pathways that I outlined last month.

The current economics profession in general, and our central banking leadership in particular, sheds even more credibility as it careens on, blinded by its own light. The process by which economic activity and resources are coaxed into being by stimulative monetary policy has reached its terminus, and the public will finally understand this dynamic over the next year.

In Part II: How The European Endgame Will Be The Death Knell For Modern Economics, we predict the coming endgame to the European fiscal and monetary crises. Doing so is becoming increasingly easier as we better understand the mindset of today's economic leaders and the shrinking number of options they have to address the issues before them. In fact, we think the shroud of awe and mystery that our grand economists have wrapped themselves in is fast-dissipating, and that the systemic pain their failures will inflict in 2012 -- initially most visible in Europe -- will finally cause the populace to look to a new school of economic thinking.

Click here to access Part II of this report (free executive summary, enrollment required for full access).

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/its-time-to-give-up-on-mainstream-economics-2/