To extract itself from several decades of deflation, Japan wants to increase its exports to the world. But Europe, too, wants to increase exports, to extract itself from its own deflation. And with inflation just barely above 1.00% in the US, America also wants to increase exports.

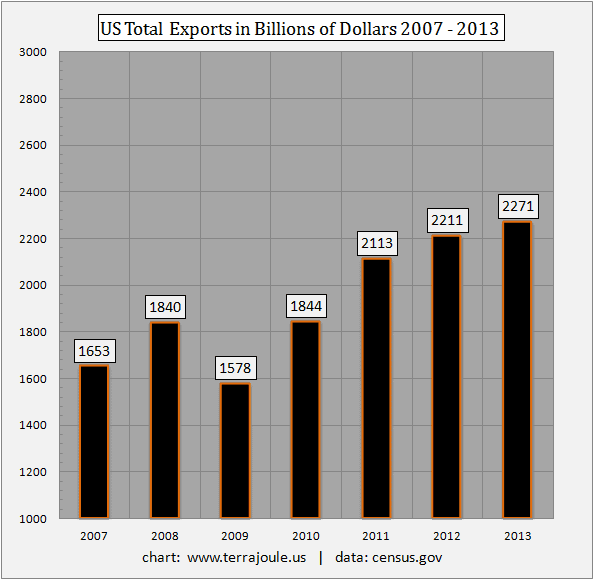

Indeed, in the most recent trade data from the Commerce Department, US exports hit an all time high as the country now emerges as a huge, first order extractor and exporter of raw commodities. But the problem here, if its not become obvious, is that all regions of the OECD want to significantly increase exports at the same time.

Understandably for the US, which sustained a consumption supercycle for several decades, the post-financial crisis period has kicked off a new trend: Americans want to consume less, and make more. Americans want to own less stuff, use less energy, and produce their own goods. In short, Americans want to sell. Indeed, it has been the stated goal of the current Administration to significantly increase exports for several years now. And, it's working.

In the latest data, total exports from the US in November reached 194.9 billion. On average for 2013, US exports are running at 2.268 trillion -- a very significant portion of our GDP:

The composition of US exports is predictably concentrated now in commodities, and especially chemicals and petroleum products.

Americans meanwhile have started to consume again to be sure. However, in conformity to many of the conditions which now characterize the US economy, the US is importing goods at a more suppressed level. 2013 imports are flat, at around 2.7 trillion, when compared to last year. Also, at this level, they are only just a little above the 2008 figure of 2.5 trillion.

Given current trends, the US will surely see successive, new all time highs in total exports. But more importantly, if the trend continues, the US is going to start running trade surpluses. For the US to flip from trade deficits to trade surpluses may bring renewed strength in the US Dollar, and, the kind of ongoing struggle that most exporters experience when trying to export through a strengthening currency.

Meanwhile, exports have been the optimal goal of the developing world, for decades. The Non-OECD has lived off trade surpluses for a long time, cleverly exploiting over-consumption in the West. Unsurprisingly, It's rather obvious that one of the problems emerging economies have had to face the past five years is the lower level of demand emanating from the developed OECD economies.

When you begin to see the challenge of a world in which everyone wants to sell, rather than buy, you can begin to understand better the fundamental problem the world economy faces: Everyone is in the same quest for end demand.

The Scarcity of Inflation

Understandably, with the economies of Japan, Europe, and the US off the lows from several years ago, many are now looking forward to an era of rising interest rates and the return of inflation.

The problem is that inflation readings not only are failing to tick up, they have been falling. Everywhere.

Inflation readings over the past two years have fallen in Europe and in the US. And in Japan, which has attacked its currency with vigor over the past year, food and energy inflation have finally started to rise to a meager 1.00% -- but this has not helped wages.

Even in the developing world, inflation has slowed down remarkably. It would seem that in the developing world too, after 15 years of very strong growth and a great industrial build-out, demand is also running at lower levels.

From a late December Wall Street Journal Article, Low Inflation Test World's Central Banks:

Inflation in both advanced and emerging economies picked up in the early stages of the economic recovery, eventually straddling central banks' inflation targets closely enough that many policy makers were charting an exit from their extraordinary monetary policies. But persistently weak demand in recent years has pushed inflation back into uncomfortably subdued territory...Fed officials have forecast consistently that inflation would pick up, but that hasn't happened...The situation in Europe is perhaps more fraught. European Central Bank President Mario Draghi has said the euro currency bloc may see a "prolonged" period of low inflation. ECB forecasts support that view, with inflation averaging just 1.3% in 2015, well below its target of just under 2%...In China, the world's second-largest economy, inflation as measured by consumer prices has fallen to below 3.5% this year from 8% five years ago. Some economists say years of state-directed overinvestment in factories and a buildup of excess capacity could push prices even lower.

So, all nations now want more inflation in order to lessen the burden of the private and public debts built up over the past decade. And also, most national economies wants to tip the balance of consumption and production in favor of production, so that the cash flows from sales rise and are also available to service past debts.

The paradox of thrift, which marked the first couple years after the 2008 crisis, is still very much with us. But the paradox of thrift has gone global now.

Interestingly, for very conservative economic thinkers, this is presumed to be a very good thing. Everyone, everywhere, making and producing more than they consume, is held up as an ideal. The problem is that someone has to consume. Otherwise, the global economy is going to tip back into overproduction. Which will, of course, aggravate deflation.

US Federal Reserve Capitulates to Low Inflation

One of the more startling revelations on the inflation question came from the US central bank in late December, when its long term forecast for inflation essentially admitted its own inability to generate inflation. Incredibly, the Federal Reserve forecast allowed that its own inflation target of 2.00% would be missed for the next two years (See: FRBM Economic Projections December 18, 2013 - opens to PDF).

Let's pause and consider the implications, here.

Since the implosion of the Tech Bubble in the year 2000, the United States has undertaken not one, but two historically aggressive monetary easing cycles. The first took rates down to 1.00% and the second to 0.0%, where we stand today. Also during that time the US spent trillions on two wars, made significant boosts to security and defense spending, and conducted fresh rounds of investment in roads and highways. After the financial crash of 2008, the US increased fiscal spending on infrastructure once again, this time on rail and renewable energy. In addition the US oversaw a sustained period of well above trend expenditures on social safety net programs.

The majority of economic observers, not only on the political right but also on the left, worried intensely about the potential effects of soaring budget deficits in the years after 2008. And yet, after more than a decade of wildly-above-trend government spending, much of which called upon use of natural resources, there is no monetary inflation to be found, and wages are stagnant.

Indeed, the only sustained inflation that can be found both in the United States and globally is sourced directly from two key areas: energy and food. Here, it's not reflationary policy but peak cheap oil, soaring populations, upgraded food diets, the repricing of fertilizer, and the decline of arable land per capita that are to blame.

The weak dollar explanation for resource price pressure has long, long faded into the past. That was a story with some relevance over ten years ago, when the sky-high US Dollar began its great decline after the bursting of the Tech Bubble, and as natural resources globally began to reprice. You could be forgiven, therefore, for concluding that the Repricing of the Planet which began in 2000 was the direct result of global monetary policy. Not so, it turns out.

Moreover, the conclusion that's now most likely is more grim: without successive bubble creation, the super-trend towards lower inflation, disinflation, or even outright deflation would have proceeded more quickly.

Mainstream Economists Are Starting to Understand

Since 1995, every bubble that has been created -- from tech stocks, to housing, to credit -- has eventually burst and deflated.

The pattern now coming into view is gaining clarity: an underlying era of secular deflation has spread slowly among the developed economies. Monetary authorities have only fought off this trend periodically, as each new reflationary effort slides backward into deeper levels of disinflation.

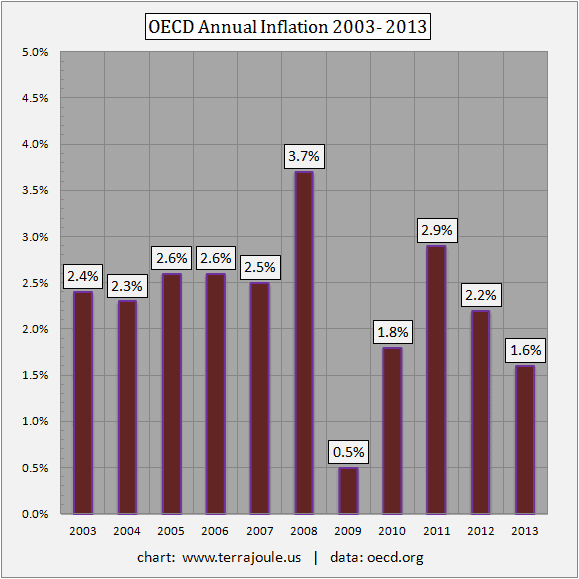

In the most recent data release from the OECD, dated January 9, 2014, inflation advanced from 1.3% over the past year to 1.5%. A change so small it barely merits attention, and is hard to distinguish from noise. Over the past five years, excepting food and energy, inflation in the OECD has only occasionally risen to the 2.00% level. And now, with food and energy prices having settled out the past two years, even OECD inflation readings including those two categories is below 2.00%. Indeed, inflation in the developed economies has fallen for the third year in a row:

A mainstream economist who finally kicked the door open on this problem was Larry Summers, who in November gave a speech to the IMF asserting a secular era of stagnation has lingered over the OECD for some time now, and the Europe and the US were in danger of turning Japanese. The Summer's speech has fostered a conversation over the past month or two, and Matthew O'Brien wrapped up the various reactions in his piece, Does the US Economy Need Bubbles to Live?:

Larry Summers thinks the economy is broken, and has been for awhile....It's not just the Great Recession and the not-so-great recovery. It's the 8 years before that too. As Summers points out, even low interest rates, deficit-financed tax cuts, and nonexistent lending standards weren't enough to overheat the economy then. Sure, housing prices boomed, but nothing else did. Inflation was low, and unemployment wasn't that low. In other words, demand wasn't excessive, but it wasn't sustainable either...Summers worries that this isn't only a story about our economic past, but about our future, too. That we won't be able to create enough jobs without bubbles, now and forever. It's a new old idea called "secular stagnation." Economist Alvin Hansen first proposed it in the late 1930s when it looked like slow population growth might slow investment, and create a permaslump. But, thankfully, the baby boom, and 16 years of pent-up consumer demand proved him wrong.

Ah, but there's the problem: The prospect for a new baby boom is very low, in an era of falling fertility rates.

Moreover, the historic energy transition the global economy has faced the past ten years is now beginning to cut in a surprising direction: high oil prices constrain the global economy from faster growth, but, cheap natural gas and coal fund the bulk of powergrid growth at relatively low cost.

In one sense, this sounds like a goldilocks world: steady, but very slow growth, with low inflation. The difficulty comes when you consider that wages and demand are weak, and global labor remains in surplus, at a time when much of the resource repricing from the past decade remains.

In Part II, Prospects for Disinflation in 2014, we look at the unlikely prospect that inflation will appear anytime soon. There is little coming in the way of wage growth, and the reserve of surplus labor--especially in the OECD--remains fairly high. We will also look at whether energy prices may rise enough to place any pressure on inflation, with particular emphasis on coal and natural gas.

Click here to access Part II of this report (free executive summary; enrollment required for full access).

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/losing-the-war-against-deflation/