The notion of preparing for cold weather has radically different meanings between geographic locations. A person living in Louisiana will have different needs than someone in Wyoming, and as such, it’s important to discuss what environments create “cold,” the types of cold, and how they create thermal injuries. There are differing schools of thought, but the following is a good cross-section that should help you get a hook set in Old Man Winter and keep his icy fingers off you as much as possible. Too often these days, people dress for the “indoors,” in which the climate is controlled. That’s fine, so long as you can absolutely guarantee you won’t be exposed to the elements. Otherwise, it’s smart to plan ahead.

Types of Cold

Ambient Cold

Cold can be defined as an absence of heat. It is the ‘de facto’ state of the universe, and as such, we are remarkably lucky to live on a planet that has heat sinks, rather than scorching heat during the day and incomprehensible cold at night. The absence of heat can generally be looked at as the by-product of the seasons. As the earth rotates around the sun, a 21.5 degree “tilt” about its axis creates uneven thermal heating and gives us the four seasons we enjoy (or hate, if you’re a tropics lover). Without that tilt, we would only have two seasons, and weather as we know it would be entirely different. So our first type of cold is ambient cold. It’s simply a lack of heat, and it’s an environmental phenomenon.

With ambient cold, we typically see less dramatic impacts, as the sun can still be shining (in the mid and equatorial latitudes, and at the poles for a solid 6-months-on/6-months-off pattern). Because of the solar angle, more light is reflected into space, and thus less hits the Earth’s surface to be radiated about the lower troposphere (where we live).

Because of this, ambient cold often seems to be “warmer” than other types. You’re still collecting some solar radiation (warmth), and even under clear, cold conditions, a tremendous amount of insulation may not be necessary.

Environmental Cold

Environmental Cold is the cold we experience due to meteorological phenomenon; it’s the combination between Ambient Cold and “x”, with x being variable weather conditions. The most common cold-inducing environmental effects are wind and rain. They can lead to deadly thermal injuries if not managed, and fortunately, they’re the conditions that we have the most influence over. If you look back to the Survival Saw, behind breathable oxygen, shelter is the second most potent impact and we can survive exposure for only around 3 hours – though in severe cases, the impacts of thermal injury will set on within minutes.

While this might seem self-evident, the first and best way of mitigating environmental cold is just simply avoidance. If you don’t have to go out, don’t! Set yourself up so that you don't have to go out or can minimize the amount of time you spend outside.

A little pre-planning here will go a long way – most of our outdoor activities during cold revolve around other things that are similarly impacted by cold: our vehicles, pets or livestock, or tasks such as collecting firewood. Insulation on or around watering troughs, raising your windshield wipers, and bringing in wood in advance of an ice storm or freezing spell, for example, will help make your job easier and keep you out of the cold as much as possible. If you live in a cold climate, consider how these temperatures will impact your vehicles, especially. Fluids left in the vehicles can freeze, and this can lead to cracked heads, hoses, and radiators, if not protected. Long story short, it behooves one to keep the garage clean enough to park one's car in it, or you may well be risking serious damage to your vehicle.

Protection Against the "X"

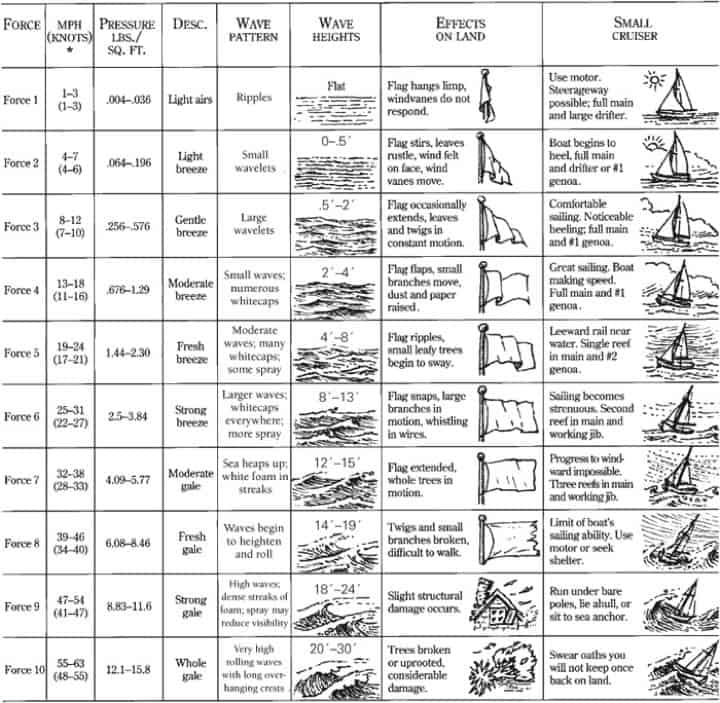

When you set out into the cold, it’s important to consider which variables you’re going to face. A stiff wind will sap the heat off your body from the exterior; this makes the ambient temperature feel colder than it is, and this is commonly referred to as “wind chill.” Wind chill can be estimated by using some pretty simple observations, called the Beaufort Scale, which is extremely well represented in the following graphic:

Figure 1: The Beaufort Scale

(Source)

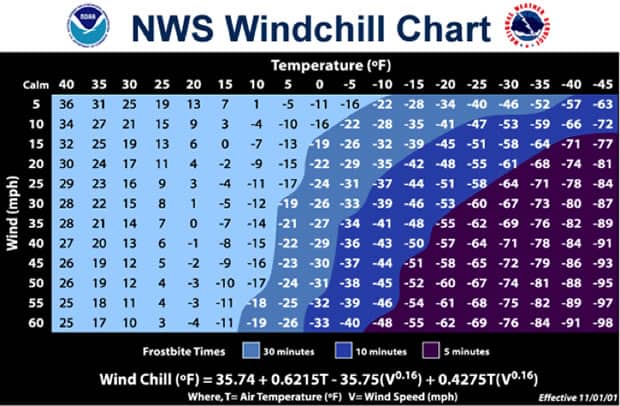

Get comfortable with the wind speeds and how they correspond to visible effects on your surrounding environment. Once you can see how the wind impacts the world around you and mentally link that to a wind speed, it’s not too much work to anticipate just how cold it will feel outside, and therefore we can plan accordingly. The following this chart put out by the National Weather Service demonstrates the wind’s impact on Ambient Cold:

Figure 2: NWS Windchill

(Source)

Preparing for the Cold

Cold is mitigated in “layers” (very similar to the “lines” concept discussed in Every Day Carry - EDC). Each additional layer is additive to and performs functions in excess of the previous layer.

Figure 3: Layers from innermost to outermost

Photo by Aaron Moyer

Base Layer

Base layers are generally thought of as thermal underwear. The function of the base layer is twofold: It traps heat close to the surface of your body and wicks away moisture. If it fails at one of these two tasks, the result is an uncomfortable and possibly unhygienic experience. Be sure to keep these clean, as the moisture these wick away is going to be warm sweat, which creates an ideal environment for bacteria. There are many types available with varying degrees of effectiveness, comfort, weight, and cost. Wool, for example, is certainly warm, but it’s often expensive. This example is Merino wool, which is a good deal lighter, but still much heavier than other options. Old polypropylene can be had for fairly cheap, but it’s bulky and not amazingly comfortable under clothes. Capilene is both thin and very effective, but a set of long underwear and a shirt can cost north of $100.

Mid Layer

The mid layer is probably the most flexible and constitutes the greatest number of wear options, overall. Without getting all REI on you, these are shirts and sweaters, referred to as “mid layer” because they go between a jacket and your underwear. Pretty simple. There are a number of synthetic fibers that are available these days, almost all of which are some sort of polyester and acrylic combination. This is for good reason; polyester fabrics generally repel liquids pretty well, don’t take flame (see melts quickly instead of catching fire), it doesn’t sustain microbes very well, and perhaps most importantly, it wicks away moisture much better than cotton. Considering these factors, they’re a good bet for long-term, hard use, and you’ll find that most ‘performance outerwear’ is made from polyester fabrics. As homage to organic Chemistry, polyesters are long-chain polymers that feature esters as the predominant functional group. They’re formed by reacting carboxylic acid and alcohol. (Gee whiz; it came in handy after all.)

Outer Layer

The outer layer is to fabric what the mid layer is to clothing types. There has been a ton of development on outer layers, and you’ll hear terms thrown around freely that sales people expect you won’t understand: eVent fabric, Gore-Tex, OmniDry, NeoShell, and so on. These generally are layers of proprietary materials stacked on one another to do exactly what we talked about earlier: keep you warm and wick away moisture. The difference between the base layer and the outer layer is that the outer layer has the additional responsibility of keeping those “x” factors off you. They have varying degrees of wind and water resistance, which generally increase with cost. These are pretty effective against “normal” cold (see: temperatures of about 40 degrees Fahrenheit and up, for limited duration) when used in conjunction with mid and base layers, once you start looking at frigid cold and protracted durations, something more insulated becomes necessary. Articles such as the insulated Climashield jackets from Propper do an excellent job of heat retention at a lightweight. A pretty elaborate analysis was provided by REI in this article: http://www.rei.com/learn/expert-advice/rainwear-how-it-works.html. This should bridge the gap between the basics and more advanced understandings of how these materials work.

Involuntary Exposure

Everyone loves running around in their performance outerwear, fully prepared for the eruption of a spontaneous adventure…but life has opportunities to spoil our plans. Whether it’s a plane wreck or getting stranded, you might not be wearing the necessary goods to keep the thermal environment tilted in your favor. Weathering yourself in this case might require a bit of improvisation. To this point, we’ve talked about the materials that are effective in keeping you alive, mainly wool and polyester blends. It’s extremely important to mention a common mantra at this point: “Cotton Kills.” This is something you’ll hear around mountaineers often; cotton doesn’t wick moisture, and in the cold, it will draw the heat off your body through sweat or any ambient moisture. If you’re out exposed to the elements in nothing but cotton, your timeline to get to shelter just got serious.

If you happen to be wearing cotton when the unexpected becomes your temporary reality, try to be as resourceful as you can. Often as not, when there are cold and rain, there are fallen leaves. Fallen leaves (brown and dry) can be used as impromptu insulation by stuffing the space between your layers with handfuls. This will create dead air space, which blocks the chilling impacts of the wind and mitigates the amount of water able to seep through your clothes. Most people know well that thermal injuries, and in specific, cold, tend to impact the most distal extremities first, which means your fingers and toes will be in jeopardy before your core. Especially your feet, as you have very little ability to prevent your feet from touching the cold, wet earth. Again, improvising can provide a good ‘temporary’ solution. Things such as plastic grocery sacks can be placed between layers of socks to keep one layer dry. If you’ve only got one pair of socks, the bag between your socks and shoes will help keep your little piggies from running to the market looking for relief from frostbite. It’s also important to note that most of your socks are made from 100% cotton. Try to find wool or synthetics that will help wick the moisture, if you know there’s cold weather coming your way. You’ll be warmer and your feet will stay drier.

Socks are the first part of footwear, so the next and possibly most important is your shoes or boots. Good shoes are going to be made from as few pieces as possible. The more stitching and pieces involved, the more places there are to spring leaks, split, and separate. While boots are outside the scope of this article, good boots will go a long ways towards keeping your feet healthy, and that’s tremendously important. Give your shoes a great deal of consideration…proper footwear depends on a tremendous amount of elements, such as intended use, style and dress code, desired load, ankle support, and tread. In short, buy shoes or boots that fit your intended uses and are known to be long-lasting.

Tricks of the Trade

Many people have heard the saying red sky at night, sailors delight; red sky in morning, sailors take warning. There are quite a few of these old colloquialisms, and there is some science behind them. To cap this article off, I’ll discuss a few and how they can help you observe what weather might be headed for your, so you can plan accordingly.

Red sky at night…

This saying has some merit, interestingly enough. Red sky is a measure of how solar radiation interacts with particulates in the atmosphere, and the particles that appear red on the visible spectrum are associated with high pressure, as these particles tend to concentrate in areas of high pressure. When you see it to your east, (in the Northern Hemisphere) that means that the high pressure is moving off, and will be replaced with lower pressure, less stable air mass. The opposite, red sky at night, means that the stable column of air is moving towards you, and decent weather will result. It’s also worth noting that the coldest weather is generally 48 hours behind the passage of a cold front. That’s because high pressure and stable air indicates that the cold air is below the warm air. Because of this, we can expect ambient cold, generally accompanied by some sunshine.

Dew on the grass, high pressure will last

Another proverb with some backing in science, the observation of water particles on the ground indicates that subsidence (the settling of cold air) has pressed moisture to the ground. This is a strong indicator of high pressure and generally indicates that you’re solidly under a stable air mass. The same thing applies to the wisdom that states if your woodsmoke is pressed to the ground, you’re under high pressure…whereas if your smoke rises quickly, the pressure is trending towards low.

Figure 4: High Pressure

(Source)

Figure 5: Low Pressure

(Source)

Horse-tails bring rain

The very high, wisps of clouds known as cirrus, or commonly “horsetails,” are really ice crystals that are in the upper levels of the troposphere. These crystals had to get to that height somehow, and that almost always means that they were “pushed” aloft by a front. Therefore, horsetails can generally be thought to preclude a front by 24-48 hours.

Figure 6: Cirrus before a front; note how it curves upwards. It is overriding high pressure

(Source)

If you can’t see your shadow…

As light passes through various types of clouds, it will be strong enough to allow you to see your shadow, or so dense that a significant amount of the radiation is “trapped” in the clouds and doesn’t let through enough light to cast a shadow. The reason for this is that clouds close to the ground are less dense and are generally created by surface heating. The puffy “popcorn” clouds (cumulus) are associated with fair weather, and you’ll be able to see your shadow. The very high clouds are too thin to block out the light that casts shadows. However, the thick banks of clouds that create light too diffuse to cast a shadow are cause by the approach of a front, more often than not (and especially in the U.S., east of the Rockies) signify that you’re going to have a significant weather change, and more likely than not, some rain.

Figure 7: Diffuse Light through Altostratus

(Source)

This is just a bit of general wisdom that doesn’t get too specific, but will make you right about the weather more often than not. Obviously, it’s meant to be used in conjunction with other verifying techniques, but give it a try and see if it doesn’t help you plan to dress for the weather.

Cheers.

~ Aaron Moyer

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/preparing-for-cold-weather/