How to Choose Firewood

In most areas, there are a few preferred species, based on several factors: cost, availability, burn qualities, etc. The species that best meet each of these criteria will vary considerably in different areas of the country.

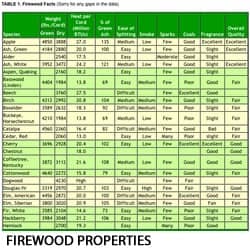

Generally, the densest (heaviest) dry wood will provide the most heat for any given amount of storage and firebox space. If convenient, the best way to shop for wood would be to figure out the cost per pound. This can be approximated by referring to charts showing the weights of various wood species. Another approach that will yield pretty much the same results is to compare various species' BTU ratings and use it to determine the cost per BTU. Note that this is not necessarily the same as cost per cord. Wet wood will need to be seasoned (cut, split, and stacked) for a year or two before you use it.

Generally, the densest (heaviest) dry wood will provide the most heat for any given amount of storage and firebox space. If convenient, the best way to shop for wood would be to figure out the cost per pound. This can be approximated by referring to charts showing the weights of various wood species. Another approach that will yield pretty much the same results is to compare various species' BTU ratings and use it to determine the cost per BTU. Note that this is not necessarily the same as cost per cord. Wet wood will need to be seasoned (cut, split, and stacked) for a year or two before you use it.

Availability is literally all over the map. In Colorado, I and most of my neighbors burn mostly pine and aspen; in Washington, Douglas fir, alder and hemlock; in Utah, pine, pinion, maple; fruitwood everywhere. I am sure there are several excellent species that I don't even know about. Many of my California acquaintances wouldn't consider burning anything but oak. If you're stumped, pay attention until you find someone with a huge stack of firewood and go have a talk with them. Better yet, if you spot them working on their stash, offer to lend a hand and you'll likely learn all you need to know.

Pay attention to where the fruit trees are in your area. Often they are neglected and in need of some love. If you know or are willing to learn how to prune them properly, folks will sometimes give you the trimmings in exchange for the work. Fruitwoods are generally among the nicest firewood you can get. If you can do small equipment repair, you might be able to trade your local tree guy for some of their trimmings.

Maple is one of my favorites; easy to split, lots of heat, long lasting and very little ash or creosote. The best wood I have ever used is madrone, which grows on the West Coast, but it is no longer legal to harvest in some areas. Avoid elm at all costs, as it gives off fumes that will make it nearly impossible to breathe and provides very little heat.

My point here is that local wisdom is your best guide; the old timers have been practicing for a while, and likely have things dialed in pretty well, so why re-invent the wheel?

Acquiring Your Wood Supply

Acquisition is a matter of finding, then buying or harvesting, your supply.

If you are buying, you need to determine the species or mix of the wood, the price per full cord (a full cord is 128 cubic feet of cut, split, and tightly stacked wood). A "face cord" is a 4 foot by 8 foot stack of wood of any length, and may contain way more or more likely way less than a full cord. Many state laws require that firewood be priced by the full cord. For convenience, 16-inch-long pieces work well: easy to handle, fit most stoves well, and easily make exactly a 4x4x8 foot stack, which is exactly a full cord. If you buy your wood, you might consider providing an easily accessible storage area that is divided into 4x4x8 sections, so you can easily tell that you are indeed getting the amount of wood you bargained for. A few years ago in Washington, my son got an order for 6 cords from one of our chimney customers. When he showed up and began delivering full, measured cords, the lady was astounded. She had been buying "6 cords" for several years, but by the time 4 actual cords were delivered and stacked, she had enough wood and was out of room...your mileage may vary.

If you are cutting your own, there are several prerequisites. You must have and know how to safely and efficiently operate a reliable, sharp, well-tuned chain saw, along with all the "politically correct" safety equipment (I strongly recommend Barnacle Parp's New Chain Saw Guide to help you get up to speed). You must have permission or the proper permits to harvest the wood. And you need a heavy-duty truck and/or trailer. It is smart to have at least two people present, in case of an accident. If you are transporting your wood, many folks make 16-inch rounds in the field, then split it up back at the ranch as time allows.

Splitting involves turning proper length rounds into wedge-shaped sections that are easy to handle and that fit your firebox. You need an area to split in (this can be a messy process, although some folks do it in low lying areas, and eventually the buildup of bark and trash cures soggy spots). Finally, you need either a power splitter or a splitting maul and a set of wedges. If you are splitting manually, turning the round upside down (base end up) often allows for much easier splitting. Again, in many cases, 16-inch length pieces usually work well. Smaller splits dry/cure faster, and are easier to light than big ones. On the other hand, big ones burn slower and will last longer. Smaller full rounds about the size of your split pieces or a bit larger can help hold a fire much longer (overnight) than equally sized splits. My best advice is to have an assortment and to experiment. You will soon learn what works best for you.

Splitting involves turning proper length rounds into wedge-shaped sections that are easy to handle and that fit your firebox. You need an area to split in (this can be a messy process, although some folks do it in low lying areas, and eventually the buildup of bark and trash cures soggy spots). Finally, you need either a power splitter or a splitting maul and a set of wedges. If you are splitting manually, turning the round upside down (base end up) often allows for much easier splitting. Again, in many cases, 16-inch length pieces usually work well. Smaller splits dry/cure faster, and are easier to light than big ones. On the other hand, big ones burn slower and will last longer. Smaller full rounds about the size of your split pieces or a bit larger can help hold a fire much longer (overnight) than equally sized splits. My best advice is to have an assortment and to experiment. You will soon learn what works best for you.

[Note: jasonw recommends the Fiskars X Series Axes for log splitting.]

for log splitting.]

Preparation & Storage

Preparation is fairly simple, with a few considerations:

Once you get your wood home, it needs to be stacked and stored properly near the entrance to the house, but not up against the wall (to prevent bug/critter problems). Your storage area should ideally be sized to hold a 3-year supply to allow for proper curing and rotation. As previously mentioned, cord-sized sections are a good idea to ensure that you're getting your money's worth. The stack should be raised up off the ground to avoid the bottom getting rotted (I use old pallets laid out under the stack). There needs to be room for good air circulation all around the stack to aid in drying/curing. And finally, there should be a good, rainproof cover over the entire top of the stack.

Last, but certainly not least, fix your favorite beverage, have a seat where you can see your stack, and smile! You're looking at warmth, comfort, and money in the bank.

~ Ed Williams

Ed Williams and his son, Eli, have been installing and caring for chimneys and their owners for over 35 and 22 years, respectively. Their service area includes most of Utah and parts of Wyoming and Idaho. Please feel free to contact them if you have any questions, observations, or interesting stories related to heating with wood.

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/preparing-your-firewood-supply/