"The task of the real intellectual consists of analyzing illusions in order to discover their causes." ~ Arthur Miller

"The task of the real intellectual consists of analyzing illusions in order to discover their causes." ~ Arthur Miller

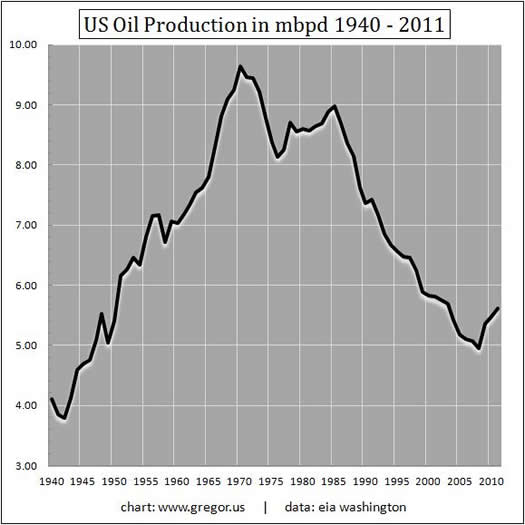

US production of crude oil peaked in 1970 at 9.637 mbpd (million barrels per day) and has been in a downtrend for 40 years. Recently, however, there's been a tremendous amount of excitement at the prospect of a "new era" in domestic oil production. The narratives currently being offered come in the following three forms: 1) the US has more oil than Saudi Arabia; 2) the US need only to remove regulatory barriers to significantly increase production; and 3) the US can once again become self-sufficient in oil production, dropping all imported oil to zero.

Let's first take a look at over 70 years of US oil production.

The US is currently enjoying its second stabilization phase since the peak in 1970. (Daily oil production has rebounded from a deep hole in 2008, from below 5 mbpd to above 5.5 mbpd). The first stabilization period lasted for more than 7 years, from 1977 to 1985. While it did not reverse the overall decline trend, which had resumed by 1990, this was certainly good news, just as our current production increases are good news. But the production history laid out graphically here is instructive and gives a clear warning: It would be unwise to herald the recent uptick in domestic production with a "new era" headline. Deepwater drilling, Gulf of Mexico, and Alaska were all "new era" events in their day as well. Or so they seemed.

Now, three respectable publications have recently cast the advent of new oil extraction in America as a kind of miracle. And indeed, technologically, the refinement of hydraulic fracturing techniques -- first used to extract natural gas, and now used to extract oil -- is miraculous. But a technique such as this, although replicable and repeatable, will not change the fact that newer, unconventional resources are developed and produce oil at a much slower rate. One year after the Black Giant of East Texas was discovered in the early 1930s, it was producing just 1 mbpd. The US no longer has resources such as this to exploit. The history of US oil production over the past 40 years should make this clear.

However, this did not stop the Telegraph of London from making triumphant assertions in their October 23 piece:

World power swings back to America

The American phoenix is slowly rising again. Within five years or so, the US will be well on its way to self-sufficiency in fuel and energy.

The US was the single largest contributor to global oil supply growth last year, with a net 395,000 barrels per day (b/d)," said Francisco Blanch from Bank of America, comparing the Dakota fields to a new North Sea. Total US shale output is "set to expand dramatically" as fresh sources come on stream, possibly reaching 5.5m b/d by mid-decade. This is a tenfold rise since 2009. The US already meets 72pc of its own oil needs, up from around 50pc a decade ago. "The implications of this shift are very large for geopolitics, energy security, historical military alliances and economic activity.

(Source)

The claims made here (or should I say the conjectures here), are completely over-reaching -- but worse, the data is completely wrong. This matters because the article was widely distributed and sustained a very popular position for several days on Twitter and in other media outlets. I have written extensively on the problematic nature of energy data that’s produced by the Energy Information Administration (EIA) in Washington and International Energy Agency (IEA) in Paris. So it’s not really surprising that the public, the average reader, cannot fact-check these numbers easily.

In Secrecy by Complexity: Obfuscation in Energy Data and the Primacy of Crude Oil, I explained how difficult it can be -- even for journalists -- to obtain a time series of commodity production and flows that is continuous, let alone understandable. For example, if one includes biofuels (which, of course, are not oil in any sense and do not contain the dense btu content of oil), perhaps one could claim that 2010 oil production in the US outpaced the rest of the world. But according to the EIA in Washington, 2010 saw China make the largest new contribution to world oil supplies at 277 kbpd (thousand barrels per day), followed by Russia at 199 kbpd, and then Canada at 153 kbpd. The United States? US oil production grew by an average 114 kbpd.

So in a world of global crude oil production currently running around 74 mbpd, we are asked to believe a new era has dawned for the United States on the back of an additional 114 kbpd? That would be funny, if it were not so ridiculous. Let’s also include the 2011 additions to US oil production, at 141 kbpd. Are you feeling excited yet? These are the volumes that will allow the US to re-conquer the world with new oil production, and wean itself off global oil imports? The New York Times is quite enthused about these “major developments,” as evidenced by this October piece:

New Technologies Redraw the World’s Energy Picture

This striking shift in energy started in the 1990s with the first deepwater wells in the Gulf of Mexico and Brazil, but it has taken off in the last decade as a result of declining conventional fields, climbing energy prices and swift technological change. The United States may now have the means to reduce its half century of dependence on the Middle East.

(Source)

Sigh. The New York Times has been selling that dream for several years now. Indeed, if you are old enough to have followed the presidential election cycle since the 1970’s, you’ll know that “energy independence” has been a standard, vague promise trotted out since the Carter Administration.

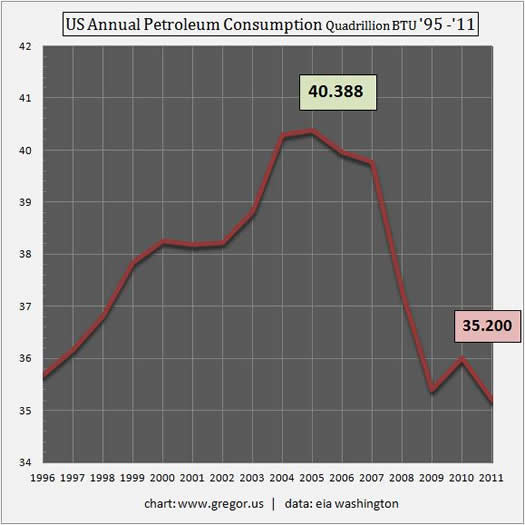

But let’s say the US did indeed want to become less dependent on foreign oil. How would the country achieve such a shift, if not through a huge increase in production? After all, the recent “rise” or stability in US crude oil production is made partially on the back of a steeper four-year production decline that carried into 2008, when the rate fell to below 5 mbpd. So far in 2011, US production of crude oil just about matches the rate last seen in 2003-2004, around 5.5 mbpd. Despite the hype, the supply side of this equation has not changed enough. Could we do something about the demand side?

So, now you know. The longest and deepest recession (actually a financial crisis and a depression) in the post-war period reduced oil consumption by 12.8%. The “miracle,” if you can call it that, of US oil independence lies not in the illusion that 5.5 mbpd of oil production can be lifted to wipe out 11.5 mbpd of oil imports. Instead, it lies in a further de-industrialization of the US economy, a huge reduction in miles driven on the nation’s roads and highways, and no doubt some energy efficiency.

Perhaps some of these are good things. Even very good things. But they are not unequivocally good things. To the extent that portions of the US economy that can shift to the power grid have done so in the past three years, for example, much of that new grid demand has been met by coal. But more broadly, it is not so much that the US is wisely and strategically conducting energy transition as a matter of policy. No, a whole tranche of the US economy has been literally kicked off oil, mainly due to the financial crisis and high unemployment, but also partly due to the inelasticity of demand in emerging markets. I would remind readers that 100% of the new demand for global oil since 2005, mostly coming from the non-OECD, has not been met by new supply. Instead, in a world of flat oil production, the resources for the developing world have come solely from a reduction of demand in the developed nations. Global oil supply is now a zero-sum game. Let’s stop litigating this fact.

Of course, no tour through the world of badly mangled energy data or energy optimism would be complete without noting the opinion of Dan Yergin. Interestingly, Yergin’s research group CERA has produced one of the best indexes of rampant cost inflation in the global oil and gas industry over the past decade. This is a key point that often eludes even the educated reader not familiar with the complexities of resource economics, and which was a ghosted irony in the New York Times article cited previously: The unconventional resources on which we now depend are complex and costly. Most important of all, they are slow. The tar sands are slow. Ultra-deepwater off the coast of Brazil is slow. However, this does not stop Mr. Yergin, who has been given free range once again to make vague, grand forecasts about future supply. In an October 31 piece in the Financial Times, he is quoted:

Pendulum swings on American oil independence

“Over the past couple of years, there has been a great U-turn in US oil supply,” says Daniel Yergin of IHS Cera, the research group. “Until recently, the question was whether oil imports would flatten out. Now we are seeing a major rebalancing of supplies.”

(Source)

It no longer amazes me to hear Yergin make such claims. U-Turn in US oil supply? A major rebalancing? Yeah, sure; whatever. This pabulum is, of course, not taken seriously by energy investors as a whole, and certainly not by some of the more notable hedge fund managers, who took it upon themselves to get out in front of oil depletion early last decade. Mr. Yergin is useful to a political complex that wishes to avoid the career risk of actually having to do something about our increasingly uneconomic transportation systems and the developed world’s dependence on oil. This is as true here in the States as it is in Europe. Indeed, why take the political risk of telling Americans they should choose to transition away from automobiles, when price will start to do some of that work regardless?

Continuing with our theme, the Telegraph of London was completely wrong when it claimed that the US now meets 72% of its own oil needs, up from 50% a decade ago. Worrying to the cause of mathematical accuracy in journalism, that 72% figure nearly describes the amount of crude oil the US must import -- which is currently running at 68% of US consumption. Moreover, given the peak and decline in VMT (vehicle miles driven), we once again confront the myth that the US economy is recovering and has new oil supply to do so. This is a nasty combination of normalcy bias, which plugs in to the wish for resurrection and the plain old fallacy of composition. A very small amount of new oil production has been blown up beyond all scale and proportion. To the Arthur Miller quote in the header of this essay, the question is: Why has the media presented this illusion now, to the American audience?

We need to examine even more closely, however, the actual prospects for lifting US oil production, were we to imagine a kind of War on Oil Depletion in the United States. (No, we're never going to extract the kerogen deposits of the Green River Formation, despite the investment-opportunity (!!) spam in your email). Environmentalists probably believe for example, especially in the wake of their victory this week on the XL Pipeline, that the US is unlikely to ever adopt a full-on, drill, drill, drill policy for oil. I think that's a mistake, and I would point to a country like Australia, which, despite a new tax on carbon, has increasingly become a single, vast territory of resource extraction.

Unfortunately, our oil transition effort has only just begun. It's still taking place only in very minor fashion, at the margin. The balance of this decade must be tackled first, and it will be felt as an ongoing battle between oil prices bumping up against a ceiling as economies repeatedly fail to recover.

In Part II: How To Postion for the Next Great Oil Squeeze, I also show the specific data on US Imports of crude oil, and why Canada, with its very slow-flowing tar sands, is hardly going to save the US, XL pipeline or not. Most importantly, I will explain how oil depletion will likely mean quite a profitable future for America's independent oil and gas companies and address the key questions: how can the average investor position themselves for the next great oil demand shock? and when will it happen? All within the context of overall, energy-induced economic decline in the OECD, as resource depletion of oil -- which remains the master commodity and the primary energy input to the global economy -- means that a higher level of economic volatility will be the new normal until energy transition unfolds more fully.

Click here to access Part II of this report (free executive summary; enrollment required for full access).

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/selling-the-oil-illusion-american-style-2/