Even though we don't know precisely how the future will unfold, we know a few things about it:

- Of the 7.5 billion humans on the planet, virtually every individual wants to enjoy a high-energy consumption “middle-class” lifestyle. As a generous estimate, 1.5 billion people enjoy a high-energy consumption lifestyle today; the remaining six billion are aspirants hungry for all the goodies enjoyed by the 1.5 billion—all goodies based on affordable, abundant energy.

- Our dependence on debt to fuel growth—more extraction of resources, more energy, more manufacturing, more consumption and more earned income to pay for all this expansion of debt and consumption—has built-in limits: debt accrues interest and principal payments, which reduce the remaining income available to spend on consumption. Our dependence on fast-rising debt just to maintain low rates of growth eventually limits our ability to pay for more consumption/growth. When most income is devoted to servicing debt, there isn’t enough left to buy more stuff or support additional debt.

- The debt needed to move the growth needle is expanding at a much higher rate than the growth it generates. While growth is stagnant, debt is expanding by leaps and bounds to unprecedented levels. (Global Debt Hits A New Record High Of $217 Trillion; 327% Of GDP)

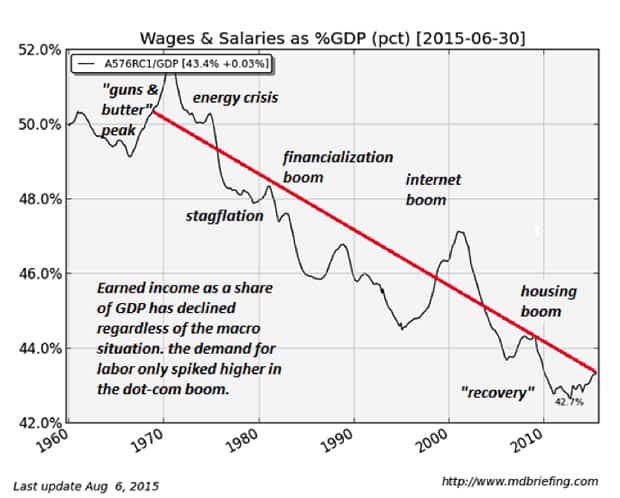

- Wages are stagnating for the bottom 90% of the workforce. We can quibble about the causes, but there is no plausible evidence to support a belief that this trend will magically reverse.

- The cost of the most valuable energy--high-density, easy to transport—will slowly but surely become more expensive as the cheap, easy-to-extract energy sources are depleted, notwithstanding the temporary boost provided by the fast-depleting wells of the fracking “miracle.”

- There are limits on our exploitation of resources such as fresh water and wild fisheries. Humans can print currency (money) but we can’t print fresh water, energy, wild fisheries, etc. If one unit of currency currently buys one liter of petrol, printing 10 more units of money doesn’t create 10 more liters of fuel.

- Creating currency out of thin air isn’t free in our system: all new currency is loaned into existence and accrues interest. As a result, all currency is a claim on future earnings. If we borrow enough from the future, and earnings remain flat or decline, eventually there’s not enough income left to support the debt service and the expanding consumption the status quo needs to keep itself glued together.

What’s the result if we add these up?

Simply put, debt-dependent consumption in a world in which wages stagnate for the bottom 90% and energy costs increase as demand outstrips supply is a system with only one possible end-point: collapse.

The Energy-Debt-Growth Connection

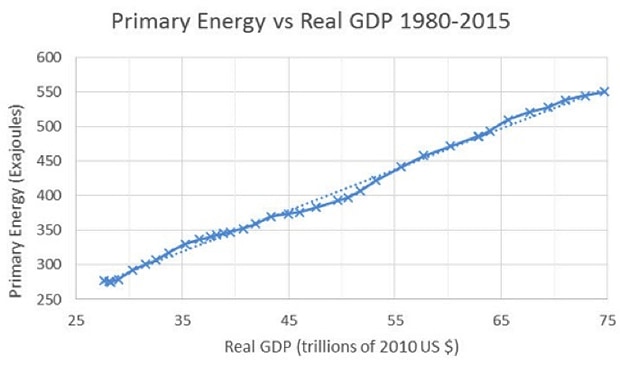

If we accept that energy will get increasingly scarce and costly, and real earned income for the vast majority of households is in structural decline, that means the global economy is in terminal trouble. As this chart shows, energy consumption per capita and GDP (gross domestic product, a measure of growth) are in near-perfect correlation: rising energy consumption per person is the foundation of economic expansion:

If energy consumption per person declines, so does GDP. If GDP/ economic expansion stalls, the global financial system--dependent as it is on the permanent expansion of debt and income to service that debt--has a problem.

In other words, energy, growth and debt are intrinsically linked. Analysts Gail Tverberg and Chris Martenson, among others, have been discussing the causal connections between energy, debt and the financial system for years. Here are recent examples of their work:

- The Looming Energy Shock (PeakProsperity.com)

- The Next Financial Crisis Is Not Far Away (OurFiniteWorld.com)

Simply put, the extraction of fossil fuel energy and the development of alt energy on a vast scale both require an equally vast expansion of interest-accruing debt, both to fund the actual extraction, processing and transport of energy and the consumers’ purchases of all the energy-intensive goods and services that keep the economy expanding.

Right now, oil and natural gas are relatively inexpensive compared to historical peaks, especially when prices are adjusted for inflation. Broadly speaking, the fracking “miracle” (based on expanding debt) has pushed supply temporarily higher than demand. (By temporary I refer to a timeline of a few years.)

The resulting collapse in energy prices, while welcome to consumers, negatively impacts energy companies' ability to seek new reserves (exploration and production), tap existing reserves that cost a lot to extract or build new alternative energy facilities on a large enough scale to matter.

As we witnessed in the 2008 spike in oil prices to $140 per barrel, soaring energy prices crush consumer spending, triggering stagflation and recession.

The solution is a Goldilocks price structure—energy prices that are not too high (for consumers), and not too low (for producers). The problem is that as energy costs ratchet higher while wages stagnate or decline, the financial capability of households and businesses to pay higher energy and debt-service costs and expand their consumption vanishes.

Something has to give: either consumption declines (triggering structural, permanent recession) or the energy sector goes bankrupt as its production costs cannot be covered by the price of energy consumers can afford to pay.

Meanwhile, the skyrocketing debt required to keep the entire status quo glued together is sapping income, reducing the every participants’ ability to pay for future growth.

These realities leave three possible futures:

- Energy prices move beyond what’s affordable, and the system breaks.

- Debt service costs rise above what’s affordable, and the system breaks.

- Both energy and debt service costs rise in tandem, and the system breaks.

Magic Technology and Wishful Thinking to the Rescue

The consensus solutions to increasingly unaffordable energy are technological: new technologies are going to make energy abundant and so cheap it’s practically free.

While it’s true that there are many alternative energy technologies in development, the reality is few make financial sense and few have the potential to scale up rapidly enough to replace oil/coal/natural gas.

Take liquid fluoride thorium reactors. The consensus is that this form of nuclear energy is reliable and safe. Yet not a single working thorium reactor is in operation. (An update on the potential of LFTR power - PeakProsperity.com)

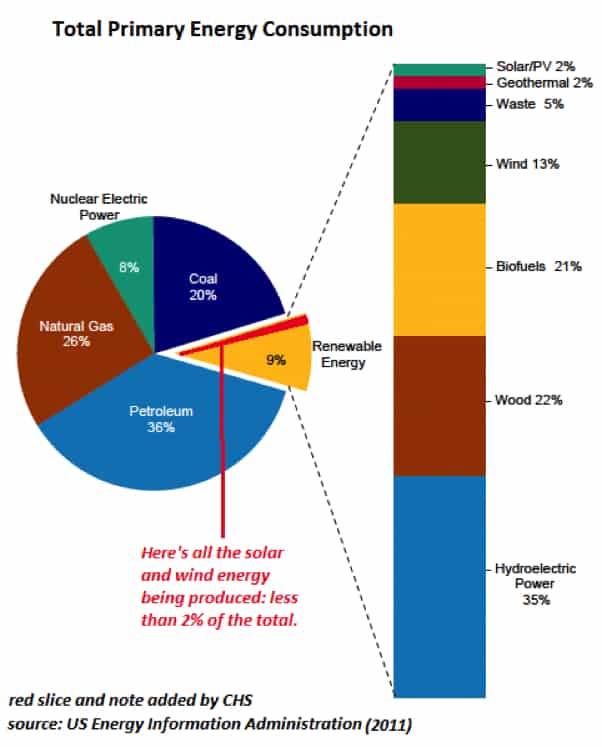

How about all those solar power technologies that are going to make electricity abundant and cheap everywhere? Magical thinking is appealing, but the reality is wind and solar make up roughly 2% of all energy consumed globally. These could double, triple, quadruple and then double again, and they wouldn't even begin to replace fossil fuels.

Even if wind/solar became dirt-cheap to manufacture, install and maintain (in the real world, we have to measure total life-cycle costs, not just the initial purchase price), these alt energy sources are intermittent, and that's a big problem for two reasons:

1. Batteries are not “free” and current technologies rely on scarce resources (lithium, etc.)

2. Utilities need to maintain significant power generation capacity to replace these sources during night, cloudy days, when the wind decreases, etc.

This means the entire infrastructure of fossil-fuel generated electricity must be maintained--a very costly requirement.

The other problem with the “electricity and storage will be nearly free” line of magical thinking is much of our transport system can't be switched to electricity--aircraft, container ships, etc.

Virtually every optimistic vision of a cheap, abundant energy future overlooks these problems, or assumes each will effortlessly be solved with some new whiz-bang technology that just so happens to be dirt-cheap.

But not all technologies that work on in lab are affordable and not all technologies scale from the lab to production on a global scale.

Maybe some lab will invent a battery based on a cheap, abundant resource like silicon, but the process of manufacture may still be horrendously expensive, i.e. require a lot of energy and costly machinery. Even if batteries can be manufactured at a low cost, they’re only serving the 2% of total energy being generated by intermittent sources.

Technological solutions are always the "answer," but the actual costs of scaling up new technologies to offset the decline in conventional oil is ignored or glossed over.

If scaling up a new energy source bankrupts consumers and producers alike, is it a solution?

Magical Thinking: Debt Doesn’t Matter

The other line of magical thinking is that debt doesn’t matter, because future growth will always provide us with enough income to service debt. As noted above, the structural stagnation of earned income means this assumption is no longer valid.

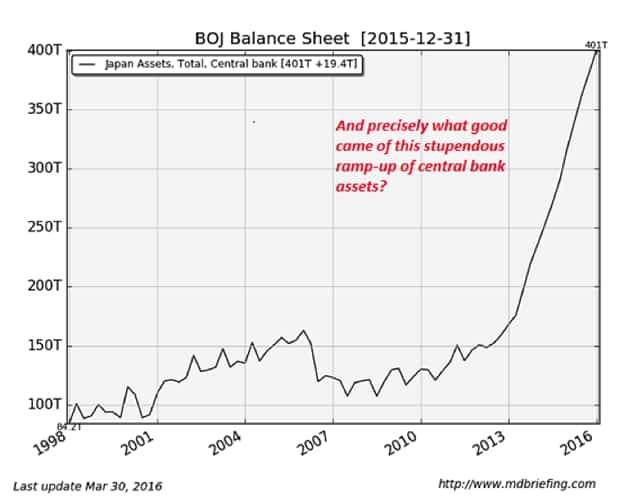

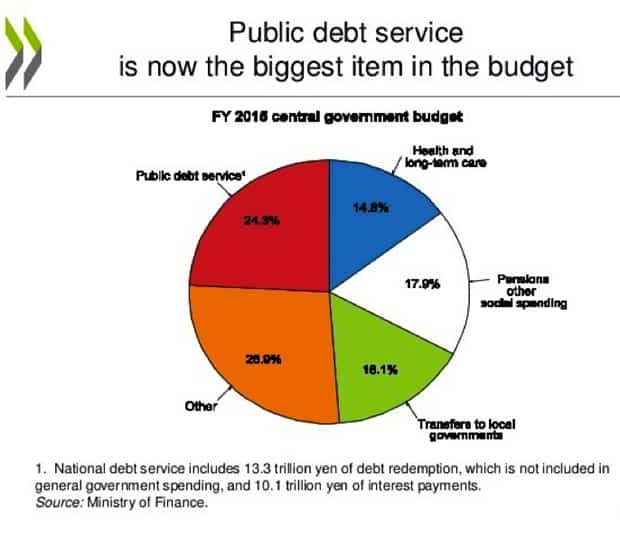

The next line of defense is that super-low interest rates will make debt practically weightless. But back in the real world, we find even interest rates near zero eventually burden governments and economies. Consider Japan, which has been running a 25+ year experiment in “debt doesn’t matter.” In 2015, the cost of servicing its astronomical debt was the largest single item in the government’s budget:

If this is the result of near-zero .1% interest rates, imagine the eventual impact of 1% or (gasp) 2% interest rates—never mind 4% or higher.

Let’s also consider the central bank balance sheet and policy that undergirds this hyper-expansion of debt. This is a chart of the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet. If this looks sustainable to you, hmm, you might want to dial back your happy-meds:

And what good came of this unprecedented expansion of central bank “monetary easing”? The net result is a near-zero growth stagnant economy burdened with exploding debt remained glued together, arguably rescued not by the central bank but by the collapse of energy prices and the one-off expansion of China’s economy.

These realities force fact-based observers into pondering a future that consumes less energy per person and generates less income and debt per person--a DeGrowth economy.

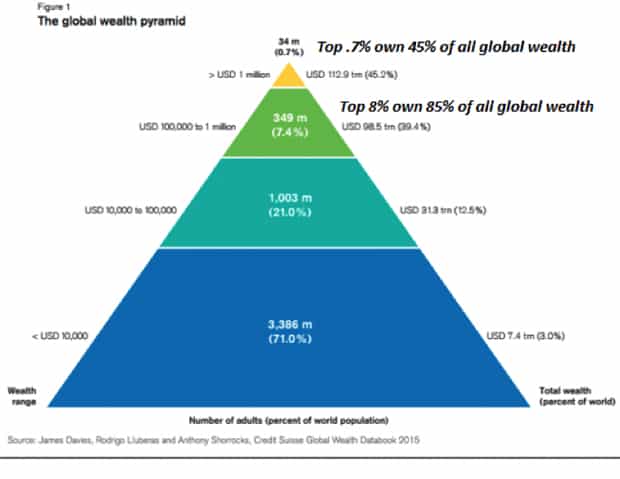

The status quo—highly centralized, dominated by self-serving elites gorging on a highly unequal distribution of wealth and income--cannot survive a structural decline in earned income and the resulting collapse of debt, or a reduction in energy consumption per capita. But humanity could do just fine.

In Part 2: A Blueprint For DeGrowth, we provide the blueprint for a DeGrowth economy that’s more sustainable than the status quo, and that leaves magical thinking at the door.

The economic/political paradigm of rising energy consumption and debt required to keep the whole status quo glued together is going away. We can’t retain the existing socio-political-financial structures of this paradigm and expect to get different results; that’s a pretty good definition of insanity.

We need new models; not just for energy consumption and distribution, but for the creation and distribution of currency and political power. The good news is: they're out there.

Click here to read the report (free executive summary, enrollment required for full access)

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/the-inevitability-of-degrowth/

Agriculture and mining account for over 60% of the water consumption in Arizona, where water is a precious commodity indeed.

Agriculture and mining account for over 60% of the water consumption in Arizona, where water is a precious commodity indeed.