Q: How much is my house worth?

A: Whatever the highest bidder is willing to pay for it.

Those of you who took an introductory Economics class in high school or college may remember learning that prices are set "at the margin". That's a fancy way to say that prices are set by the person (or people) willing to pay the most.

This person willing to pay top dollar is called the "marginal buyer". Most of us don't really think about him much, but he (or she) is very, very important.

Why? Because the marginal buyer not only determines price levels, but also their stability and degree of volatility. The behavior of the marginal buyer, as well as the degree of competition for his/her "top dog" spot, sets the prices of nearly every asset class held by today's investors.

Imagine for a moment an auction room, filled with people holding their bidding paddles. A rare Picasso painting is brought to the block. Paddles all around the room compete furiously as the auction starts; but as the bid price rises higher and higher, fewer and fewer paddles participate in the bidding. Pretty soon, it's down to just two bidders dueling back and forth with one another. Then, after a stunningly high bid of $106.5 million dollars, no more paddles are raised. The marginal buyer has been found. No one is willing to outbid his price. (For the record, this is exactly what happened back in 2010 when Picasso's Nude, Green Leaves and Bust came up for sale.)

This example contains several important elements for price-setting. First: the marginal buyer's last bid is what ends up setting the final price. And second: the intensity of competition determines how high the marginal buyer's bid will go (if no one else was willing to offer more than say, $10 million, it's unrealistic to expect that the marginal buyer would have still put in a bid as astronomically high as $106.5 million).

Now imagine what would have happened if our marginal buyer above hadn't shown up for the auction. Maybe he got stuck in traffic, or decided he'd rather own a tropical island instead of a wall hanging. How much would the painting have sold for then?

It would have sold at a price lower than the losing bidder's last offer. Without our hero in the room, the losing bidder would have become the new marginal buyer. And without the threat from a competitor with deeper pockets, it's quite likely our new marginal buyer would have been able to secure the painting at a substantially lower price.

Bubble Territory

The takeaway from the above is that prices are set by two things: the upper limit that the marginal buyer is willing to pay, and how intensely the competition from other buyers pushes him towards that limit.

This is just as true for stocks and housing as it is for fine art.

And we're now seeing some concerning signs that the marginal buyers, as well as their competitors, are beginning to go on strike across those asset classes.

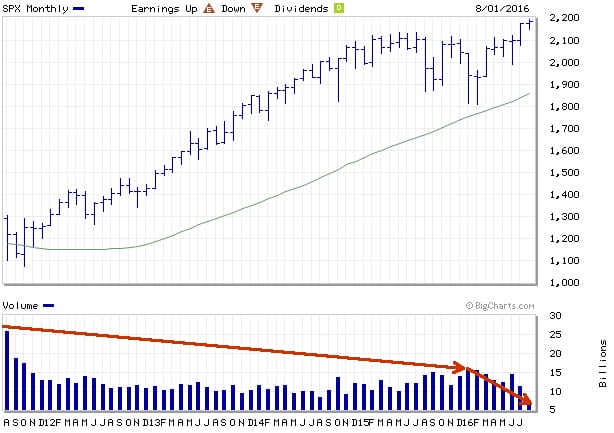

Let's look at the stock market. For the past 5 years, stock prices have been powering higher. Good, right? Well, not so good when you look at the volume underlying these prices. Volume has been in decline over this period, and the rate of decline has accelerated since the beginning of this year. This means fewer buyers -- less competition -- pushing the marginal buyer to spend more. Which likely explains why the S&P 500 index is roughly unchanged from where it was 2 years ago:

(Source)

And as for the marginal buyer, it's increasingly looking like that role is being filled today by the central banks instead of from a wide pool of institutional and retail purchasers (as a proof point: the Bank of Japan now owns over 60% of its nation's ETF market). Putting aside for a moment what an abomination this circumstance is to free and fair markets, having prices set by a central bank is a huge threat to price stability. Why? Because no one else can compete with an entity able to print an infinite amount of thin-air money at will. The gap between what a central bank is willing/able to pay vs the next marginal buyer is tremendous; so if the central bank ever pauses its buying, prices can drop precipitously.

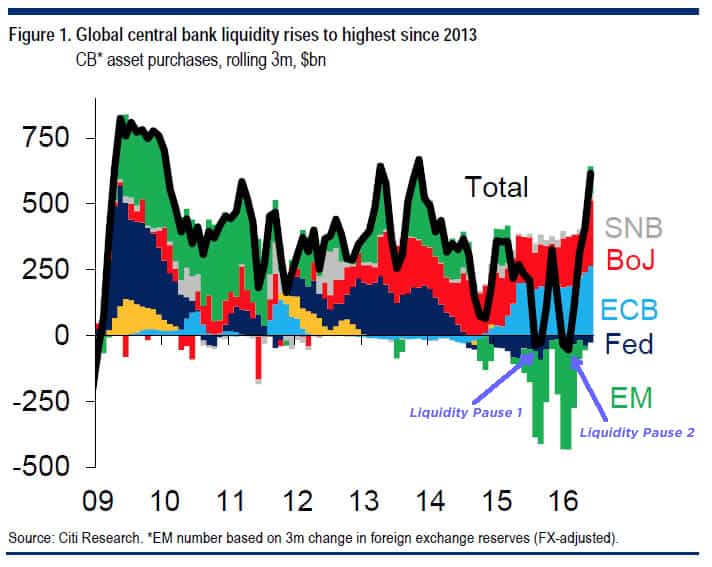

Hmmm, why does that sound familiar? Oh, that's right...that's exactly what happened last August, and again at the beginning of 2016 when the S&P went into violent free-fall. Note how those plunges line up exactly with the two moments over the past year when the world central banks' liquidity spigot was at its lowest:

In a related vein, observe how the historic stick-save the S&P experienced from March of this year onwards corresponds to a sudden and massive ramp-up in net liquidity by the central banks.

We now live with a market dependent on a single marginal buyer: the central banking cartel. This raises some very concerning questions. What happens when it can no longer print at the same rate? (Prices will collapse). Or even worse: What happens if it keeps printing at this rate? (At some point: hyperinflation, as the purchasing power of the world's major currencies gets destroyed)

The Housing Market: Poised For Another Crash?

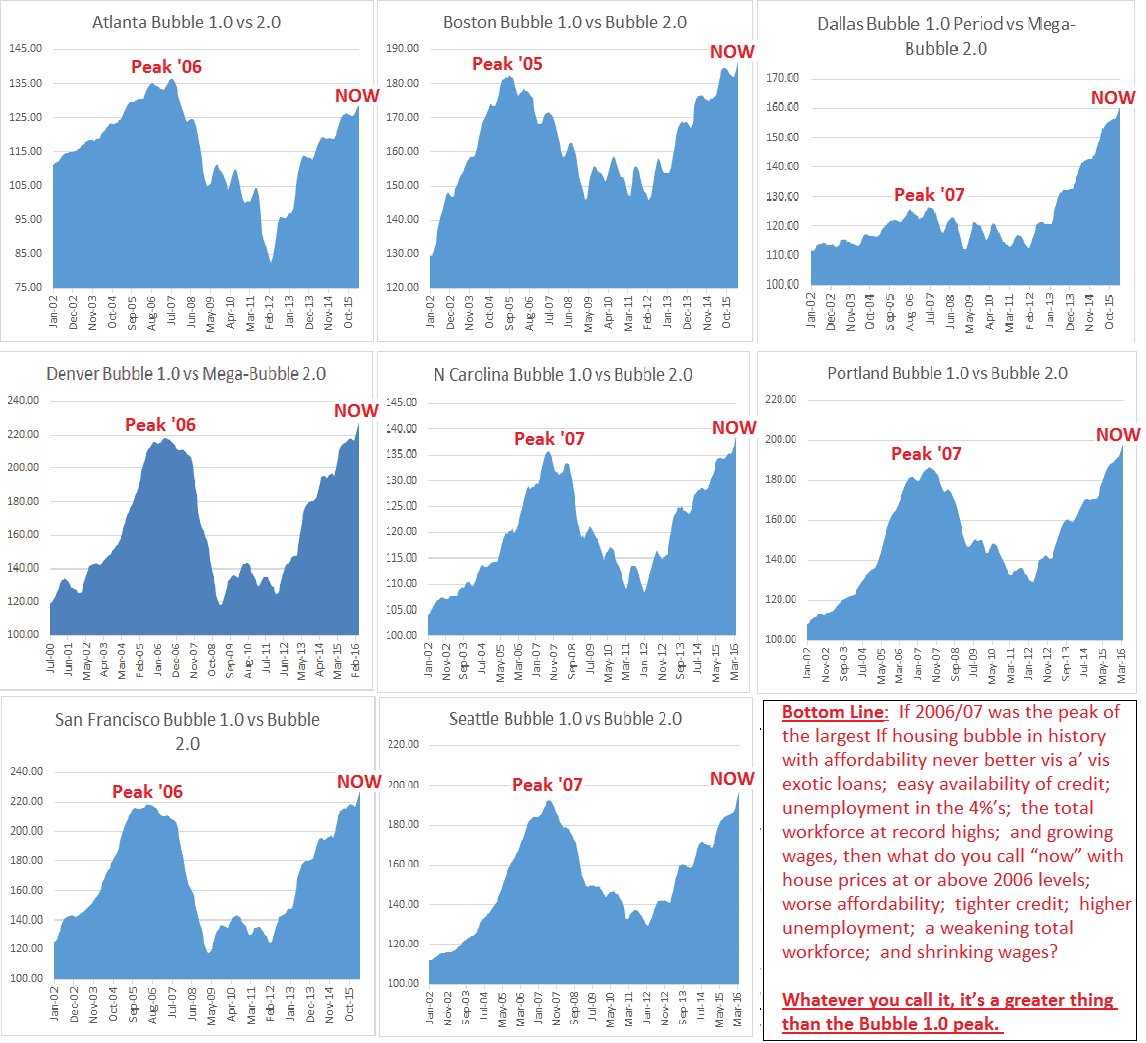

Housing is similarly at risk. Prices in many markets have been bid up past their previous 2007 bubble highs:

(Source)

This recklessly swift return to bubble heights is being indirectly driven by the same central bank money printing we see in stocks. The liquidity of new capital flooding across the world is seeking a return as well as safety. At this point, the US is one of the few markets offering both positive stock returns and (barely) positive interest rates.

So tons of overseas money is flowing in. In popular housing markets like San Francisco, Seattle, Manhattan and Vancouver, the marginal buyer over the past half-decade has largely been foreign, looking to get his cash away from the market and confiscation risk of his native country (I've written often about the impact that the wave of over-asking-price, all-cash offers has had on Silicon Valley, where I lived until recently).

Again, the key question is: What will happen if that current marginal buyer disappears? This is not an academic question; it's a very real risk in these markets. Countries like China are tightening their capital controls, making it harder and more punishable to get money over to the US.

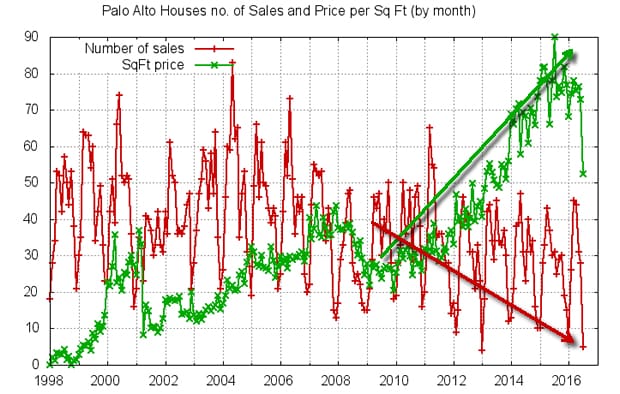

In Silicon Valley's Palo Alto bellwether market, you can clearly see transaction volume decreasing as prices first skyrocketed and are now flattening (sound like the S&P?):

(Source)

And in Vancouver, the marginal buyer there seems to have vaporized practically overnight following the passage of a new 15% property tax on foreign purchasers. The following article was published last month:

"The Deals Are Collapsing" - Vancouver's Housing Bubble Has Burst

Good luck collecting from the Chinese oligarch buyers.... or even finding them.

But the most dramatic impact will be on future transactions. With the soaring uncertainty about the future rate of home appreciation, and the availability of "greater Chinese fools", buyers will be far more pessimistic and cautious about paying the asking price, or engaging in the kinds of ridiculous auctions profiled here before, such as that of a house valued at $16 Million, selling for $68 Million "In 7200 Seconds."

Quoted by FP, Dan Morrison, chairman of the Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver, said he’s heard of instances of Canadian buyers and sellers who backed out because of the uncertainty in the market. Philipp said one of his offices reported four cancelled deals as a result of the tax, while another reported five failed transactions on Friday alone, with one directly tied to the tax.

“There’s a domino effect here. One deal collapses, there’s so many other deals impacted by that,” Philipp said.

“I’m getting people coming to our open houses saying, ‘this means the prices are going to come way down,’” said Re/Max realtor Dave Vallee.

And now this, published just 2 weeks later:

Zolo, a Canadian real estate brokerage, keeps track of MLS home sales in real-time and reports prices as an average rather than the “benchmark price” used by the REBGV. It currently shows a major correction underway in most Metro Vancouver markets. According to the website, the City of Vancouver currently has an average home price of $1.1 million, down 20.7% over the last 28 days and down 24.5% over the last three months. The average detached home is $2.6 million, down 7% compared to three months ago.

Note how the sudden disappearance of the marginal buyer can set off a vicious downwards chain reaction, as it exposes how far prices must fall to become affordable to the next marginal buyer. And, of course, in a correcting market, few want to attempt to catch a falling knife -- so the potential population of marginal buyers shrinks as they sit on the sidelines waiting for the carnage to abate.

That's the main point of this article: the marginal buyer can evaporate faster than you think. That is the nature of an asset bubble's unavoidable destiny to "pop".

History, both recent and dusty, is full of this lesson and the folly of failing to learn from it, as this popular chapter from the Crash Course explains:

As an investor in a market this full of over-inflated asset bubbles, the prudent move is to hedge. "Hedging" is the practice of allocating a minority percentage of your investments to safer or inversely-correlated holdings relative to the majority of what's in your portfolio. Simply increasing the percentage of your portfolio held in cash -- particularly during times of apparent overvaluation, like now -- is an easy and practically risk-free hedging step that anyone can do.

In our guide How to Hedge Against A Market Correction (free executive summary; enrollment required for full access), we explore the standard range of hedging techniques that are commonly used to offer portfolio protection and/or upside during a market downturn. These include stops, inverse and leveraged securities, shorting, options, and futures. Even if you ultimately do nothing, at least make that a calculated decision. Don't put yourself at risk of being one of the millions who will look at their statements after the next market correction and lament: Why didn't I consider protecting what I had?

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/the-marginal-buyer-holds-the-pin-that-pops-every-asset-bubble/