There is a revolution underway in education being driven by digital technology. Like all technologically fueled upheavals, this revolution requires creative destruction of the current industry, which is resisting the revolution even as it attempts to embrace the parts that might preserve the status quo.

This is an old story: Huge labor-intensive industries with enormous fixed costs face competition from new technologies and new systemic processes. Those earning a living within the old industries resist the destruction of the institutions and cost structures that have supported them, but resistance is futile, for the new technologies and processes are faster, better, and cheaper, often by an order of magnitude.

Though the entire spectrum of education from preschool to doctoral studies is being revolutionized, I will focus on higher education, which is already being creatively disrupted by digital technologies. All that is needed to fulfill the revolution is a parallel advance in systemic processes.

The Old System: Systemic Scarcity of Media and Knowledge

To understand the revolution, we need to start with the historical roots of the current system, which arose from a profound scarcity of knowledge and instruction. In the ancient world, storing information was extremely expensive. Even after Gutenberg’s printing press made mass-produced books available, books remained expensive. Only a wealthy household could afford to buy more than a few books.

Informed instruction was similarly limited. Instruction in universities was often one person reading a text aloud to a classroom of students; this is the source of Cambridge University’s longstanding academic rank of “Reader.”

The scarcity and high cost of written media led to the primacy of the oral lecture, as the only way to share knowledge was to concentrate students in one small geographic area to hear these lectures.

Despite the ubiquity of relatively inexpensive books, higher education in the 20th century remained essentially unchanged from the medieval model of students gathering to hear lectures drawn from large libraries. This high-cost structure kept universities elite institutions, offering finishing schools for the upper-class and a narrow channel of meritocracy for the best and brightest of the lower classes.

World War II and the Advent of the Factory Model

The advent of global war required a rapid expansion of industry and managerial skills on an unprecedented scale. Unlike previous wars, oil, technology, industrial production, advanced research, and management of these complex systems became paramount in World War II. In response, the U.S. Federal Government ramped up the nation’s small elitist institution of higher education into a vast factory of universities and colleges producing millions of educated workers to serve the emerging knowledge economy.

This Factory Model was based on the principles of mass production. College students attended the same lectures as hundreds of others and studied the same textbooks as thousands of others. The system of accrediting each college created an illusion of parity between institutions. While an Ivy League diploma was recognized as being worth more than a standard-issue diploma, any bachelor’s degree was deemed adequate proof of academic achievement.

This Factory Model yielded a three-part system: the traditional elite of academia, research, and the professional schools (i.e. graduate and doctoral programs), mass-produced four-year bachelor’s degrees, and a two-year community college system that served two roles: as preparation for a bachelor’s degree and as a vocational school.

The need for white-collar managerial workers exceeded the output of college graduates in the 1950s and 1960s, so supply and demand favored college graduates, who found good-paying jobs relatively quickly and opportunities for advancement relatively expansive.

Colleges expanded quickly, using federal and state funds to construct campus buildings. Costs were held down by modest salaries for non-tenured instructors and flat management structures.

In effect, a hodge-podge system tossed together in a national crisis became institutionalized. This is best revealed by this question: If we could start from scratch now, how would we design an effective, responsive, accountable, low-cost higher education?

Answers vary, but it certainly wouldn’t resemble today’s failing, costly, obsolete system.

Expensive, Obsolete, Failing

Though it pains its advocates to hear, the reality is that America’s system of higher education is expensive, obsolete, and failing. Though proponents finger reduced state-level spending as the cause of higher tuition and fees, this claim ignores the many structural causes of higher costs, including bloated layers of management, soaring salaries and benefits, costly building projects, and so on.

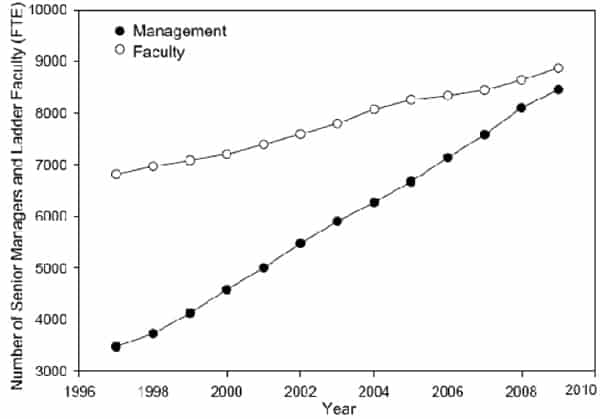

Consider this chart of one University of California campus's employment of professors and administration. If we extrapolate the lines, there will be more highly-compensated administrators than there will be professors teaching in the classrooms.

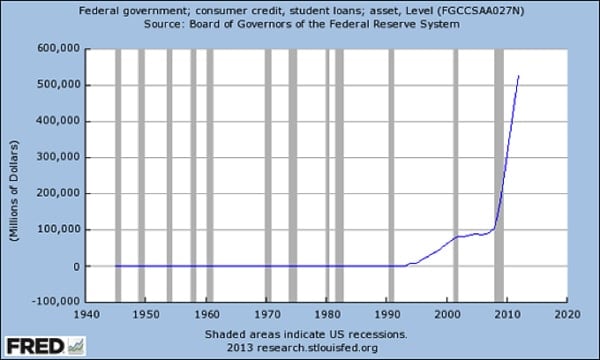

Federally backed student loans are skyrocketing by hundreds of billions of dollars. U.S. government-issued student loans ($560 billion) now exceed the entire gross domestic product of entire nations; for example, Sweden ($538 billion). Non-Federal student loans total another $500 billion, bringing the total to over $1 trillion.

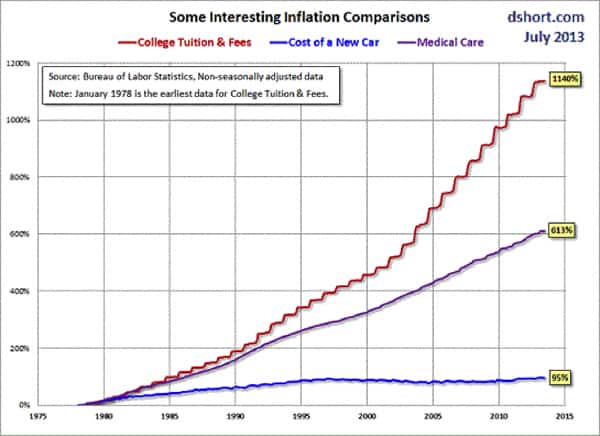

While the cost of higher education has skyrocketed (tuition is up 1,100% since 1980), the value of college education and diploma has declined. One national study, Academically Adrift, found that over one third of college students “did not demonstrate any significant improvements in learning” critical thinking and other skills central to success in the new economy. From this dismal record, we can extrapolate that another third gained marginal utility from their investment of tens of thousands of dollars and four years of study.

Google is widely viewed as a bellwether of the new economy. It is noteworthy, then, that Google has found that academic success has little correlation with being productive in the workplace. Lazlo Bock, Senior Vice President of People Operations at Google, made the following comments in an interview published by the New York Times in June 2013:

One of the things we’ve seen from all our data crunching is that G.P.A.’s (grade point averages) are worthless as a criteria for hiring, and test scores are worthless. Google famously used to ask everyone for a transcript and G.P.A.’s and test scores, but we don’t anymore…. We found that they don’t predict anything.

What’s interesting is the proportion of people without any college education at Google has increased over time as well. So we have teams where you have 14 percent of the team made up of people who’ve never gone to college.

(Source)

Doing well in college—earning high test scores and grades—has no measurable correlation with being an effective worker or manager. This is incontrovertible evidence that the entire higher education system is detached from the real economy: Excelling in higher education has no discernible correlation to real-world skills or performance.

The Consequences of Cartel

What is striking about these runaway costs and failure to prepare students to thrive in the new economy is the stunning lack of accountability. The higher education system continues to maintain it is cost-effective and successful even as evidence piles up that it is unaffordable, failing, and obsolete.

This lack of accountability and runaway pricing are hallmarks of cartel capitalism, a variation of monopoly that offers an illusory veneer of competition. In the present system, colleges maintain a state-granted monopoly on accreditation. If you want a college degree, you have to pay the cartel its price, regardless of the education’s quality. There is no accountability for the poor product because students have nowhere else to go for a diploma but the cartel.

What Has Changed

The U.S. economy has changed in fundamental ways since the heyday of the Factory Model of Higher Education in the 1950s and 1960s. In that era, the U.S. maintained a near-monopoly on capital and industry, as war-ravaged Europe and Japan were still rebuilding their shattered economies. The rapid expansion of the consumer economy demanded an equally rapid expansion in the white-collar workforce of managers and marketers, and those with college diplomas were a scarce commodity who could command a premium on the labor market. Health care was cheap and economic growth robust; overhead costs were low; and it behooved companies to offer stable employment, low-cost benefits, and pension plans.

The 1970s upended many aspects of this high-growth era. Energy crises bled the economy of efficiency and purchasing power, and the era of high wages for low-skill factory work gave way to the first wave of automation, computerization, and robotics.

This structural shift from industrial to post-industrial employment fueled a systemic need for workers with advanced knowledge of computers, software, and related technical skills, as well as a secondary pool of workers able to deploy these new technologies in every sector of the economy: defense, design, communications, marketing, human resources, government, finance, engineering, etc.

The Factory Model could adjust to this new need by expanding curricula in these new fields while keeping the traditional departments and schools on a continued expansionary track.

Demographics played a role as well; the 60+ million Baby Boom that had begun entering college in the mid-1960s reached its college-age apogee in the 1970s.

The economy of the 2010s is undergoing a change just as dramatic and wrenching as the transition from industrial to post-industrial. The economy—and competition for capital, skills, goods, and services—is global. Overhead costs such as healthcare have soared, making hiring workers an expensive proposition. With roughly 40% of the workforce holding a college diploma, the scarcity of college-educated workers has been replaced by a surplus of workers with university degrees. (Only 5% of adults had a college degree in 1940.)

Granting more advanced degrees does not magically create positions for those holding freshly issued diplomas. Instead, it seems degree inflation is at work: what once required a high school diploma now requires a bachelor's degree, what once required a bachelor's degree now requires a master's degree, and so on.

In effect, a four-year college degree is becoming the entry-level minimum, replacing the high-school diploma. Further up the food chain, master's degrees are also in surplus, pushing many ambitious youth into PhD programs in the hope that a PhD will guarantee a high-paying job.

Alas, there is a growing surplus of people with PhDs in a number of fields. Some claim the unemployment rate for PhDs is very low, but these surveys do not measure under-employment; i.e., Did the PhD take a position that only required a lesser degree? (see The PhD Bust: America's Awful Market for Young Scientists—in 7 Charts)

New Paradigms Arising

The Higher Education cartel is perfectly happy to encourage degree inflation (at enormous expense, of course), but this zeal for issuing student-loan-funded diplomas fails to address two structural disparities: the one between the skills needed to prosper in the emerging economy and the skills colleges are providing students, and the widening income/wealth/education gap between the wealthy and the non-wealthy.

As higher education costs soar, the gap between wealthy and poor families widens as non-wealthy students are forced to become debt-serfs to pay for college. A system that forces poor households to shoulder student loans for decades in return for marginal-utility college degrees is not just immoral, it is recklessly predatory. Yet this is the system Higher Education supports and defends.

There is a profound disconnect between the Higher Education cartel and the economy and what higher education should cost in a world where information, instruction, and knowledge have fallen to the cost of bandwidth; i.e., near zero. What was once costly and scarce (knowledge and instruction) is now nearly free and abundant, readily available on any digital device anywhere in the world with a connection to the Web. There is no need to concentrate students in a campus with a library; every web-connected digital device is a library and university combined.

In Part II: The New Education Models Offering New Hope we explore the emerging rise of radically cheaper, more effective, and more accountable systems despite the institutional resistance of the Higher Education cartel. We discuss this new Nearly Free University model and how families and households can make use of these innovations as they become mainstream.

Click here to access Part II of this report (free executive summary; enrollment required for full access).

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/the-needed-revolution-emerging-in-education/