Growth. It's what every economist and politician wants. If we get 'back to growth,' servicing debts both private and sovereign becomes much easier. And life will return to normal (for a few more years).

There is growing evidence that a major US policy shift is underway to boost growth. Growth that will create millions of new jobs and raise real GDP.

While that's welcome news to just about everyone, the story is much less appealing when one understands the cost that come with such growth. Are we better off if a near-term recovery comes at the expense of our future security? The prudent among us would disagree.

Resurrecting American Export Strength

It’s easy to be skeptical that America could once again be a titan of global exports.

For a very long time, that role has mostly been relegated to countries in the developing world. America as an export economy? Somewhere along the 50-year transition from industrial manufacturer to voracious consumer, Americans have lost touch with such a remote possibility. Indeed, this phase of America's economic history is now quite settled.

A multi-decade outsourcing wave has left US workers to concentrate in the financial sector -- an over-weighting of talent that we would come to regret after the crisis year, 2008.

Since 2009, though not well advertised, Washington has been pursuing a quiet policy to boost exports in nearly every sector, throwing investment capital at port and rail infrastructure, and getting the message out to regulators and state government. Now, after some very notable gains in which exports have advanced to nearly 14% of GDP, the President in his State of the Union Speech made it clear: The US would no longer cede a labor and manufacturing advantage to the rest of the world.

With that declaration, notice was served. It was perhaps not a coincidence when, the following day, the Federal Reserve articulated a zero-interest-rate policy that would be sustained for years. The US dollar reacted immediately and promptly returned to its downtrend. Has a new industrial policy now been unveiled?

(Painting: Alfred Bierstadt, 19th Century: Mt St Helens and Columbia River)

Rivers of Coal

The small city of St. Helens, Oregon sits astride the Columbia River, 25 miles closer to the Pacific Ocean than Portland. Over the past two years, a consortium of coal shippers and coal producers has been searching along the Pacific Northwest coast for a place to construct new export terminals. Coal, which is mined in the Powder River Basin of Wyoming and which often travels long distances to power stations in the American South, would also find easy rail routes to Asian markets through the ports of the West Coast. Rebuffed already by Bellingham, WA, north of Seattle, and then rebuffed again by Longview, WA, north of Portland, the industry is trying once more -- this time at St. Helens.

To understand this persistence, one has to appreciate the current juncture in world coal markets. Global oil supply has been coming up against a ceiling for seven years now, since 2005. As a result, much of the world is trying to access increasingly more BTUs through natural gas and coal. Asia, which has built tremendous coal capacity, is a relentless user of coal. And US coal mines, older and with much higher extraction costs, are able to take advantage of rising world coal prices.

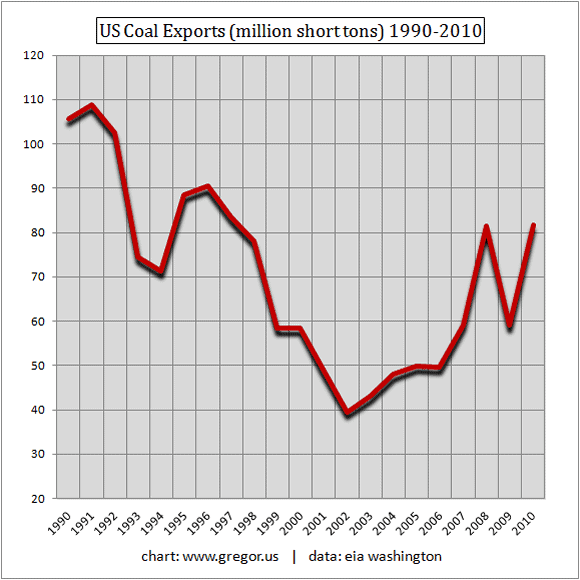

Moreover, as the US has been transitioning to natural gas for over 30 years to create electricity, that trend is only accelerating as its own coal plants age and retire. (see Regulation and the Decline of Coal, Smart Planet, January 2012, by Chris Nelder). The combined effect has caused a reversal in the long decline of US coal exports, which began to turn higher in 2002:

From a low of 40 million short tons at the start of the last decade, US coal exports have recovered and doubled to 80 million short tons as of 2010. One of the fastest-growing subsets of our coal exports has been metallurgical coal, which has soared since 2008, climbing 60% alone in 2011, over the prior year.

More broadly, the US is already in position to become an exporter, not only of refined oil products, but of other energy products, too. For example, much of the additional refining capacity that was added to existing infrastructure last decade now serves as spare industrial capacity to export US oil products, such as gasoline, diesel, and other fuel oil.

The deep and sustained cut that Americans have made to their own oil product consumption is thus being converted to exports. And with such high levels of structural unemployment, it does not appear that Americans will account for any new call on their own energy resources anytime soon.

Unless of course, we use those energy resources -- not for idle consumption, but for production.

New Energy Equations

As many are aware, the most gaping, yawning price discount found in the world today is in the comically cheap BTU found in North American natural gas. At less than $3.00 per million BTU, the energy content in natural gas can be purchased now at an 85% discount to the BTU content of oil. That is a value proposition and a pricing vacuum that -- save for the typically long time frame of energy transitions -- simply cannot stand.

Even if it takes 20 years to wean automobile-dependent economies off oil and back to electrified transport, someone, somehow, will find a way to perform physical tasks with natural gas that were previously completed using oil. As we know from history, it took Europe quite some time to transition from the Age of Wood to the Age of Coal, but the first country out of the gate was Britain, and the results were transformative. Something “like” this transition is happening today in the United States, because US demand for electrical power, produced from natural gas, coal, wind, and solar, is rising on a relative basis to our previous oil consumption.

For now, let’s leave aside some of the problems we will eventually run into as we hit the natural gas resource base harder. There will be environmental pressures, and constraints on water usage and water safety. And though it seems unlikely today, with natural gas trading at decade lows of $2.75/million BTU, there will eventually be a move higher in price. After all, North America is also gearing up to export natural gas, with proposed terminals in British Columbia and the US Gulf Coast.

The question is, should the US use this incredibly cheap BTU for export, to catch the much higher world price for LNG -- or should the US use this cheap energy as a competitive advantage, to make cheap electricity as a manufacturing input?

It appears the US is going to do both.

Already a certain virtuous circle is developing. Increased natural gas extraction is driving the need for more drilling equipment and energy infrastructure. This has induced global companies to revive metalcraft and steel operations in the depressed American Midwest. An intriguing story in this regard is the investment that Vallourec of France is making in Youngstown, Ohio, which will produce specialized steel tubing for the oil and gas industry. Surely the fact that the US has some of the lowest electricity rates in the developed world is part of the attraction.

Getting the Government on Board

Boosting the extraction of natural resources will not be without deleterious effects.

As I explained in the January 3, 2012 report A Punch to the Mouth: Food Volatility Hits the World, the massive increase in US exports of food is wonderful economic news for the US farmer. But it also means a greatly expanded use of fertilizers, and smooths the delivery of a world price for food -- which American consumers must begin to pay. In food prices, and now in oil prices and coal prices, Americans must now bid for their own natural resources in a booming world market for commodities. Equally, many communities are discovering that natural gas extraction, oil and coal shipments, and the prospect of new export infrastructure are either dangerous to the environment or simply not an industry wanted by local communities.

Despite public perception, Washington is hardly antagonistic towards increased energy production, except in the most superficial, rhetorical way. Meanwhile, many of the agencies in Washington have directed their attention towards a re-industrialization of the US, and exports in particular.

The Department of Transportation (DOT) has directed a lot of its spending towards rail and port infrastructure in the past several years. A review of the DOT’s Tiger Grants since 2009 reveals wave after wave of targeted investments in the national ports of Miami, Los Angeles, Providence, Vancouver/Portland, and many others, with special attention to rail connectivity. The upsurge in port infrastructure investment is not lost on the shipping industry either, which began in early 2010 to note the rapid growth from the first round of TIGER grants from the previous year.

When President Obama originally announced the administration’s goal to double exports by 2015, it was not taken very seriously. In a New York Times piece in January 2010, a former head of the Council on Foreign Relations was quoted as saying, "How will he perform this miracle? It really is a mystery." Indeed, if you attended university anytime since 1980 and studied economics while there, you learned that America’s industrial era was mostly over. The 1990s put a fine point on that lesson: The US would create products conceptually at home, and have the products manufactured abroad, pocketing the arbitrage of cheap labor. That equation only accelerated in the past decade as cheap coal powered foreign manufacturing centers, primarily in Shenzhen China, while oil costs rose.

But this past week, President Obama laid bare the country’s new intentions:

We can’t bring every job back that’s left our shore. But right now, it’s getting more expensive to do business in places like China. Meanwhile, America is more productive. A few weeks ago, the CEO of Master Lock told me that it now makes business sense for him to bring jobs back home. Today, for the first time in 15 years, Master Lock’s unionized plant in Milwaukee is running at full capacity. So we have a huge opportunity, at this moment, to bring manufacturing back. But we have to seize it. Tonight, my message to business leaders is simple: Ask yourselves what you can do to bring jobs back to your country, and your country will do everything we can to help you succeed. So my message is simple. It is time to stop rewarding businesses that ship jobs overseas, and start rewarding companies that create jobs right here in America. Send me these tax reforms, and I will sign them right away. We’re also making it easier for American businesses to sell products all over the world. Two years ago, I set a goal of doubling U.S. exports over five years. With the bipartisan trade agreements we signed into law, we’re on track to meet that goal ahead of schedule. And soon, there will be millions of new customers for American goods in Panama, Colombia, and South Korea. Soon, there will be new cars on the streets of Seoul imported from Detroit, and Toledo, and Chicago. I will go anywhere in the world to open new markets for American products.

No doubt a good portion of this rhetoric is election-year posturing. That said, the data shows us that exports as a percentage of GDP have soared since Obama came to office. And while part of that ratio is due to punk GDP growth, the US is stepping up its export of industrial machines, medical equipment, telecommunications and transportation equipment, civilian aircraft, and engines.

However, from its current hollowed out position, the US is still seeing its greatest growth in commodity exports. That is, in everything from grains such as corn and wheat, to cotton, and even gold. For example, by value, the petroleum products discussed earlier are now America’s largest export.

This points to a constraint: If the US is going to export mainly commodities during its long road back to the export of finished goods, then it will be even more important to cap any rise in the US dollar.

In Part II: Prepare for the Collapse of the Dollar, we discuss the growing clarity around the big changes that are afoot to create an exports-driving jobs 'recovery.'

But it comes at the cost of drastically weakening our currency and sending increasingly strategic and depleting domestic resources overseas. Essentially, inflation and scarcity will increasingly become the themes of the future.

We address the key questions concerned readers should be asking: Is this a price worth paying? What does this future look like and how should I be positioning for it?

Click here to access Part II of this report (free executive summary; enrollment required for full access).

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/the-price-of-growth-3/