In the conventional view, there are two kinds of revolutions: political and technological. Political revolutions may be peaceful or violent, and technological revolutions may transform civilizations gradually or rather abruptly—for example, revolutionary advances in the technology of warfare.

In this view, the engines of revolution are the state—government in all its layers and manifestations—and the corporate economy.

In a political revolution, a new political party or faction gains converts to its narrative, and this new force replaces the existing political order, either via peaceful means or violent revolution.

Technological revolutions arise from many sources but end up being managed by the state and private sector, which each influence and control the other in varying degrees.

Conventional history focuses on top-down political revolutions of the violent “regime change” variety: the American Revolution (1776), the French Revolution (1789), the Russian Revolution (1917), the Chinese Revolution (1949), and so on.

Technology has its own revolutionary hierarchy; the advances of the Industrial Revolutions I, II, III and now IV, have typically originated with inventors and proto-industrialists who relied on private capital and banking to fund large-scale buildouts of new industries: rail, steel manufacturing, shipbuilding, the Internet, etc.

The state may direct and fund technological revolutions as politically motivated projects, for example the Manhattan project to develop nuclear weapons and the Space race to the Moon in the 1960s.

These revolutions share a similar structure: a small cadre leads a large-scale project based on a strict hierarchy in which the revolution is pushed down the social pyramid by the few at the top to the many below. Even when political and industrial advances are accepted voluntarily by the masses, the leadership and structure of the controlling mechanisms are hierarchical: political power, elected or not, is concentrated in the hands of a few at the top. Corporations are commercial autocracies; leadership is highly concentrated and orders are imposed on the bottom 99% of employees with military-like authority.

Social Revolutions Are Not Top-Down

But there is another class of revolution that does not share this hierarchical structure, nor does it manifest in the large-scale, top-down power-pyramids of the state and private corporations: social revolutions are bottoms-up affairs, lacking centralized leadership and hierarchical control mechanisms.

Social revolutions eventually influence the state and private sector, but they do not require the permission, funding or leadership of these hierarchies; as a rule, social revolutions drag the state and corporate sectors forward, kicking and screaming, as the social fabric and values of the populace change and the state and corporate sector cling to the status quo.

Examples of recent social revolutions include the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s, the Counterculture of the 1960s, and the gay rights movement. The leadership of the state resisted each revolution, and was essentially forced to adapt to the new social order as it became mainstream.

Once corporations figured out ways to profit from the transformed social order, they quickly introduced new products and fresh marketing: all-Caucasian advertising, for example, gave way to targeted ethnic advertising and mixed-race national advert campaigns.

When social revolutions are suppressed by the state, they may spark a political revolution as the socially oppressed come to see the overthrow of the autocratic political order as a necessary step towards liberation.

In other cases, social revolutions may have little immediate impact on the political stage. Faith-based social secular movements--for example, the Second Great Awakening in the early 19th century-- were not overtly political; their eventual political impact (temperance, woman’s rights and support for the abolition of slavery) may manifest decades later.

In summary: social revolutions may generate political waves, but they need not be overtly political to do so, nor do they rely on political, financial or technological hierarchies to transform society.

The Decline of Social Groups and the Erosion of the Social Order

Robert Putman’s 2000 book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, documented the decline of social connections and what we might calling belonging in American society with reams of data. This erosion of social bonds is not limited to social groups such as bowling leagues; it is secular, spanning every social type of connection from family picnics to community and neighborhood groups.

If we extend Putnam’s findings to the core human bonds of family and friendships, we find the same fraying of social ties; people have fewer close friends, are more isolated and lonely, and family relationships are increasingly superficial or characterized by alienation.

The factors feeding this broad-based decline of connectedness and social capital are many: the nation’s economic mode of production has changed, requiring two incomes where one once sufficed, and globalization has increased both the demands on those with jobs and the number of adults who have fallen out of the work force.

This winner-takes-most economy has been accompanied by the rise of political divisiveness, a brand of politics that fosters us-versus-them disunity and the erosion of common ground in favor of demonized opponents and all-or-nothing loyalty to one party or cause.

The technological revolutions of broadcast television and radio homogenized the mainstream media even as they provided superficial substitutes for social engagement. The technologies of social media, mobile telephony and narrowcast echo-chambers of uniform opinion have created even more addictive forms of distraction that are not just shredding social connectedness—they’re destroying our ability to form and nurture social bonds, even within the family.

This dynamic was explored in a recent essay in The Atlantic, Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?

Any careful observer of present-day family life would add that the addictive draw of mobile telephony has also damaged the parents’ generation and the family unit itself.

Cui Bono: To Whose Benefit?

Longtime readers know I often begin an inquiry with the time-tested question: cui bono, to whose benefit? Who has benefited from the erosion of the social fabric and social capital, from the politics of divisiveness and the mass addiction to the technologies of superficial connectedness?

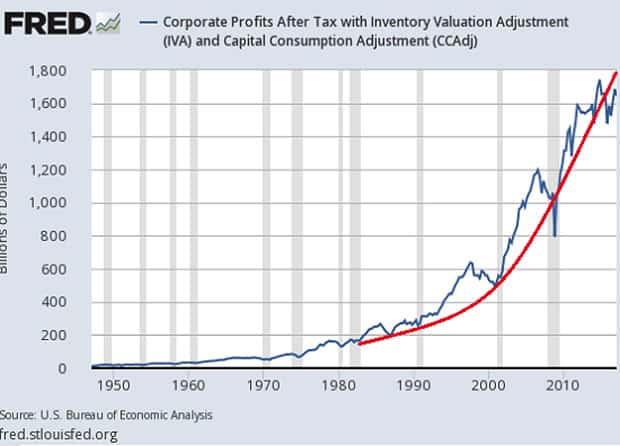

While we can take note of soaring corporate profits, and draw a causal connection between these profits and the modern-day “always connected to work” lifestyle of high-productivity corporate employees, it’s difficult to argue that corporations have benefited directly from the loss of social capital that characterizes American life.

Rather, it seems that the corporation’s relentless pursuit of narrowly defined self-interest, i.e. maximizing profits by whatever means are available, has laid waste to boundaries between work and home life as collateral damage.

In a similar fashion, purveyors of smartphones and the software and content that render them so addictive don’t necessarily benefit directly from the destruction of intimate, authentic social bonds, but they certainly have prospered from the feeding of the smartphone addiction. Once again, the loss of authentic social connectedness is collateral damage.

While it seems quite clear that political groups have fueled divisiveness to their own benefit, does the state (government in all its forms) benefit from the fraying of the social order? It’s difficult to discern a direct benefit to the state, though it might be argued that a fractured populace is easier to control.

But the erosion of the social order has gone beyond fracture into disintegration, and it’s hard to see how class wars and social disunity benefit the state, which ultimately relies on some measure of social unity for its authority, which flows from the consent of the governed.

It's Time To Take Our Future Back

In Part 2: Rescuing Our Future, we focus on the self-evident truth that governments and corporations cannot restore social connectedness and balance to our lives. Only a social revolution that is self-organizing from the bottom-up can do that.

And we detail out the specific steps each of us can and should take to develop the values and skills required to form and maintain authentic social wealth—the wealth of friendship, of social gatherings, of belonging.

It takes courage and independence to swim against the toxic tides of our economy and society. The good news is that true wealth is within reach of everyone. The steps we each need take are clear; it's just a matter of having the will to invest the time and effort.

Do you have it?

Click here to read the report (free executive summary, enrollment required for full access)

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/we-need-a-social-revolution/