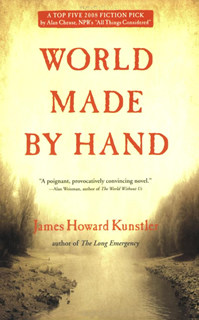

After the second novel in my World Made By Hand series (The Witch of Hebron) came out in 2010, I was beset by indignant reviews and angry letters from female readers over my depiction of gender and class relations further along in the 21st century.

After the second novel in my World Made By Hand series (The Witch of Hebron) came out in 2010, I was beset by indignant reviews and angry letters from female readers over my depiction of gender and class relations further along in the 21st century.

The fictional future economy I described was, in its broad outlines, similar to the future sketched by Chris Martenson and his stable of writers — a re-set to a far more local, much less complex, and downscaled economy, with a lot of formerly modern comforts and conveniences missing from the picture. In my fictional world of Union Grove in far upstate New York, the electricity was no longer running, the Internet was dead, giant corporations and government had withered away, motoring was history, paper money worthless, and a lot of common institutions (courts, schools, supermarkets) no longer functioned. This was an economic order very different from what we’re familiar with now, and I had to construct a plausible social order to go with it.

To step back a moment, permit me to explain that I chose to depict economic collapse in fiction because so many of us had published non-fiction books and articles on the subject that, for all their merits, left out what it would look, feel, and taste like to live in that deeply transformed future society. I wanted to get to readers through the other side of their brains, to give them a vivid emotional sense of a plausible future. I also thought that a lot of the current so-called apocalyptic fiction, movies, and TV shows were just plain stupid, that they misunderstood the forces actually in motion that would drag us kicking and screaming into the new times, and what those times would actually be like. And, of course, I was fed up with zombies, vampires, and all the other clichéd trappings of story-telling that hitched a ride on the nervous zeitgeist.

The characters in my novels lived very differently than people do in these late days of turbo-petro-industrialism. The economy of their town and the county surrounding it — the extent of normal travel in the new times — was centered on agriculture and the activities that supported it and derived from it. The division of labor had changed drastically in my fictional world, household management especially. Without microwave ovens, washing machines, heating furnaces, and other mechanical slaves that we take for granted, running a household required a lot more work. It was my heuristic judgment (i.e., guess) that such conditions would likely propel work assignments back to more traditional arrangements between men and women, especially because the care of very young children takes place in the home and, despite the wishful propaganda of our times, such care happens to fall mostly to mothers among the higher primates. (The vaunted role of “house-husband” might be improbable if it were not for the fact that so many “breadwinner” jobs today can be done by anybody, male, female, or someone in between.)

Anyway, the reaction to this fictional experiment was surprisingly pugnacious. High and low, far and wide, women denounced my book in formal reviews and casual emails. There was a unifying theme to them, though: a refusal to consider the possibility that social relations might change no matter what happened to the economy. That, and outrage that anyone might suggest a retrograde path for the recent achievements of feminism. It seemed self-evident to me that a lot of this achievement was provisional, depending on larger macro historical trends. That idea alone was greeted, in my replies to reader emails, by the sharpest opprobrium, since it was assumed that the political victories of recent decades have become permanent installations of the human condition. I recognize that, as a principle of politics, privileges and rights attained are rarely given up without a fight. But I wondered at the failure of imagination I was witnessing, especially among educated women readers.

Relations between men and women were not the only feature of the altered social landscape in the fictional future of World Made By Hand. I also created a character named Stephen Bullock whose role in the county had become, in effect, feudal lord, though he disliked thinking of himself that way. I had imagined that Bullock, a shrewd, erudite lawyer who inherited a well-managed farm, had acquired the land of his floundering neighbors and attracted a cohort of able-bodied adults, who had lost their livelihoods and property, to live and work on his establishment, which the townspeople of nearby Union Grove had taken to calling a “plantation.” Bullock’s people, the former car dealers, pharmacists, realtors, and other jetsam of a collapsed industrial-technocratic economy, had “sold” their allegiance to him in exchange for food, security, and community — he had allowed them to build a “village” for themselves at the center of his property. They now labored together in teams or work-gangs to produce a lot of value from Bullock’s land, tending crops and livestock, making value-added market products (whiskey, cheese) from the stuff they produced, running a sawmill, and so on. In exchange, they were well-housed and fed, and led an ordered existence in very uncertain and fretful times. Bullock himself is often portrayed as conflicted by his role, which includes the additional (reluctant) duty of serving as local magistrate in the absence of functioning courts. Thus, I delineated a future that was tending toward what we understand as feudalism. That proposition was greeted with only slightly less consternation by readers than my outlook for male/female vocational relations.

The reason I am explaining all of this is to emphasize that these issues of how a society orders itself are freighted with a heavy burden of emotional cargo, wishes, assumptions, bad memories, fears, resentments, and grievances, which surely accounts for our trouble buying into any vision of the future not in accordance with what’s familiar in our particular moment in history. The stickiest element in my notion of the future might be stated as the issue of social hierarchy: that human beings inevitably fall into unequal status categories, and that the future may hold new status and class arrangements that might seem strange to us today. In the best world, of course, people should be equally free to pursue happiness, or to be all that they can be, but even in an ideal society people will land in one status category or another. In that ideal socio-political system we might also expect a certain elasticity of movement, depending on the choices and actions taken by individuals in their lives, and this “upward mobility” was indeed the engine of the American Dream for much of our history — so the loss of it would be a very harsh indeed on the national psyche.

There shouldn’t be any question that social animals, which people are, universally dispose themselves in hierarchies. The argument is often made that tribal people enjoy something like absolute equality or democracy in small bands, but I’d argue that that is a sentimental fantasy of the sociologists. Rather, simple societies have simpler hierarchies or pecking orders. So, it isn’t a question of whether human societies of the future will present hierarchical qualities, but rather what scale and degree of complexity they will exhibit, how their economies will be organized, and what will be the character of their hierarchy. Clearly, these propositions make a lot of people uncomfortable — to which I’d answer that one of the imperatives of our time for serious people is to learn how to get comfortable with being uncomfortable, because that’s how things are going to get for a while.

In Part II: The New Disposition of Things, we take a close look at the ways in which our current society is most likely to change, whether it wants to or not. The end of cheap, plentiful resources is almost sure to have seismic and retrograde effects on our way of life, our social relations, and our economic systems.

Those who understand the direction of these changes and invest today in positioning themselves for a resilient, graceful entry into this future will find themselves much better prepared (physically, financially, and emotionally) than those who blindly hurtle towards reality’s coming wake-up call.

Click here to read Part II of this report (free executive summary; enrollment required for full access)

This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://peakprosperity.com/class-race-hierarchy-and-social-relations-in-the-long-emergency/